Artist team: Suraksha Acharya

Energy technologies: evaporation engine

Annual capacity: 360 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne.

An architecture team from India has designed a series of colorful, futuristic towers that harvest energy from water evaporation.

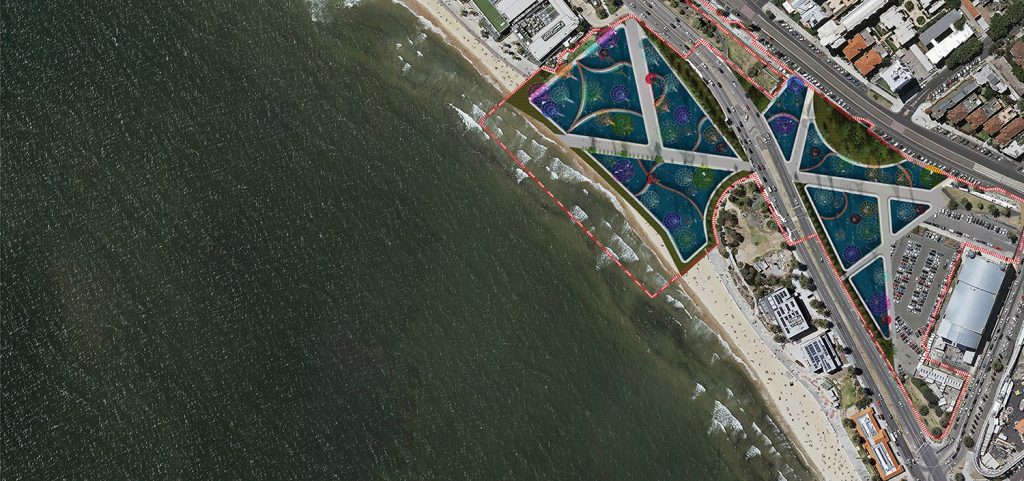

Designed for St Kilda Triangle as part of the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne, HydraSpore Symbiont beautifies and scales a biophillic technology first pioneered by Ozgur Sahin, an Associate Professor from the Department of Biological Sciences at Columbia University.

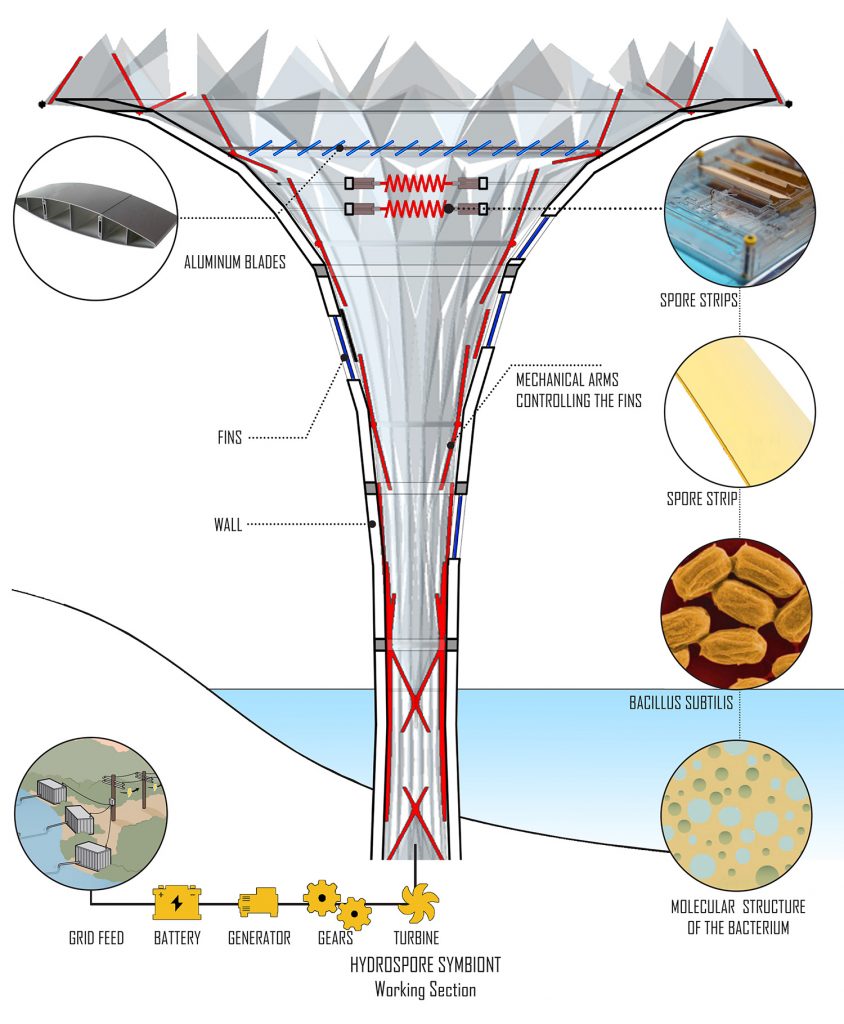

Sahin discovered that bacterial spores known as Bacillus subtilis exhibit significant mechanical responses to changes in relative humidity. In high humidity, the spores expand. In low humidity conditions, they contract. The oscillation between these two states contains energy that can be harvested and converted into electricity—as long as it is possible to control humidity and maintain constant motion.

While researching technologies for their LAGI design, Suraksha Acharya and her team sought an energy source that goes beyond household names like solar, wind, geothermal and hydro. They looked 50 years into the future for inspiration, searching for new natural resources to tap into. Then they stumbled on the research from Columbia University.

Artist team: Suraksha Acharya

Energy technologies: evaporation engine

Annual capacity: 360 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne.

“Something about creating energy from evaporative water really resonated with us,” Acharya says over Skype. They were intrigued, she adds, by the concept of an “infinite resource which is available everywhere, works in most climates in any part of the world, and can be scaled and replicated to power whole towns and cities.”

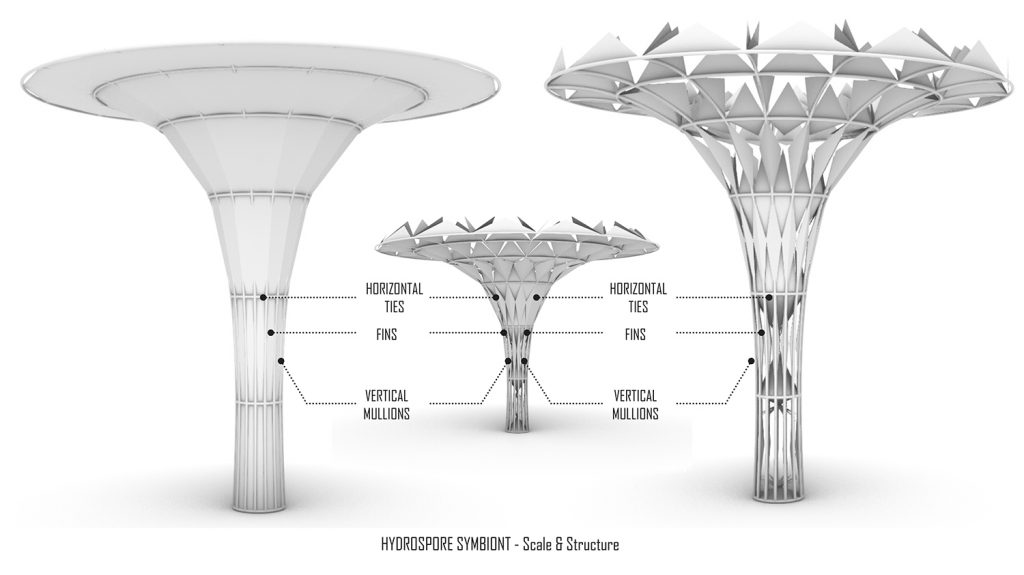

Each Hydra-Spore tower, ranging in diameter from 10 to 20 meters and about 20 meters tall, sits in pools of five-meter-deep water. At the top of each tower are crescent-shaped mechanical arms connected to engineered acrylic strips containing bacterial spores, the team explains in their artistic narrative.

As the humidity rises within the closed tower, the expanding spores push out the mechanical arms. When they reach a certain point, the arms cause the fins on each Hyda-Spore to open, allowing water vapor to escape. Eventually, the open tower dries out the spores, which closes the fins and allows vapor to rebuild within the column.

“The expansion and contraction of these spore strips leads to the production of work which is converted to mechanical energy and then into electrical energy. As the humid air rushes out of the vents above and pulls cool air into the tower, a turbine located in the neck of the structure spins to power an electrical generator.”

Artist team: Suraksha Acharya

Energy technologies: evaporation engine

Annual capacity: 360 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne.

It’s pretty heady stuff, but Sahin, an award-winning scientist who has achieved international acclaim for his research, has demonstrated the technology has a number of potential applications. In theory, it is powerful enough to move a car! But most exciting? Harvesting energy from evaporation has the potential to address both energy and water scarcity at once.

Also, given that 70 percent of the Earth’s surface is covered in water that is constantly evaporating, we’ll never exhaust this renewable resource. Compared to coal, let’s say. Or oil.

One might wonder whether intermittence is a concern, since humidity is constantly in flux. It is, though in this Nature article, Sahin and company argue that it’s possible to control for that. “Natural thermal energy storage capability of water is potentially sufficient to match realistic power demand variability,” the authors conclude—”a dramatic result for a renewable energy source that depends on variable environmental conditions.”

Artist team: Suraksha Acharya

Energy technologies: evaporation engine

Annual capacity: 360 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne.

Using the same principles as Sahin’s research, but adding the kind of aesthetic flair befitting a LAGI design, Acharya’s team envisions using tall towers that take advantage of higher wind speeds to facilitate evaporation more effectively than horizontal designs. Bold and colorful, they would make a dazzling addition to any site.

“Hydra-Spore Symbiont Park is designed to encourage social interaction,” according to the designers. “The multicolored structural fins and their dynamic movement—breathing as if alive—enable visitors to see the evaporation cycle at work and learn about this incredible spore which can exist in a dormant state for hundreds of years.”

The team has also created pathways through the artwork, surrounded by green belts that would encourage people to relax and learn about this exciting new method of generating clean, renewable energy.

LAGI’s co-directors Elizabeth Monoian and Robert Ferry are thrilled to see this creative application of Columbia University’s research, which they’ve been watching for several years.

“We were delighted to see Suraksha Acharya’s use of evaporation engines. With the fins opening and closing it will appear as if the artwork is breathing, and in a way it is. The evaporation cycle that pulls water across the entire surface of the Earth up into the atmosphere ebbs and flows with the cycle of the sun. Hydra-Spore Symbiont is a beautiful microcosm of this elegant system that brings greater awareness of it while generating carbon-free electricity from its power.”

Like many LAGI participants, designing a land art generator was a first for Midori Architects, a small startup based in Chennai. But it won’t be the last.

“It’s been a wonderful experience,” says Araycha of their participation in the competition. “I loved it, and our team enjoyed it as well.”

Tafline Laylin is a freelance communicator and journalist who strives for global environmental and social justice. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, The Atlantic, OZY.com, and a variety of other international publications.

Related Posts

2 Comments

Add comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

[…] Read more […]

[…] Read more […]