Founding Story

In 2008, we—Elizabeth Monoian and Robert Ferry—were newly married and living in Dubai. One evening in October, overlooking Ski Dubai with a bottle of wine, we began a conversation that would set the Land Art Generator Initiative in motion: how might artists and designers help shape the clean energy landscapes of the future?

Living in the UAE at a moment of rapid transformation, we were inspired by the scale of ambition around us, the desert landscape, a lineage of land art among Emirati artists, and our shared concern about climate change. That night, we began to imagine a new platform—one that invited creatives from around the world to engage directly with renewable energy as a design medium.

We asked ourselves questions that still guide LAGI today. What if the next generation of skyscrapers integrated concentrated solar power or solar updraft technologies—passively cooling interiors while generating energy for entire neighborhoods? What if cities were populated by living buildings that functioned like canopy trees in a forest, converting sun and wind into electricity while regulating their microclimates? As clean energy scales from buildings to districts to cities, what role could artists and designers play in ensuring that these infrastructures contribute meaningfully—and joyfully—to public space?

At its core was a simple provocation: what if a new generation of land artists used renewable energy technologies as their material?

The first LAGI “manifesto,” written that October as part of a grant proposal in the UAE, was unsuccessful. We lacked funding, but we were convinced the idea was worth pursuing.

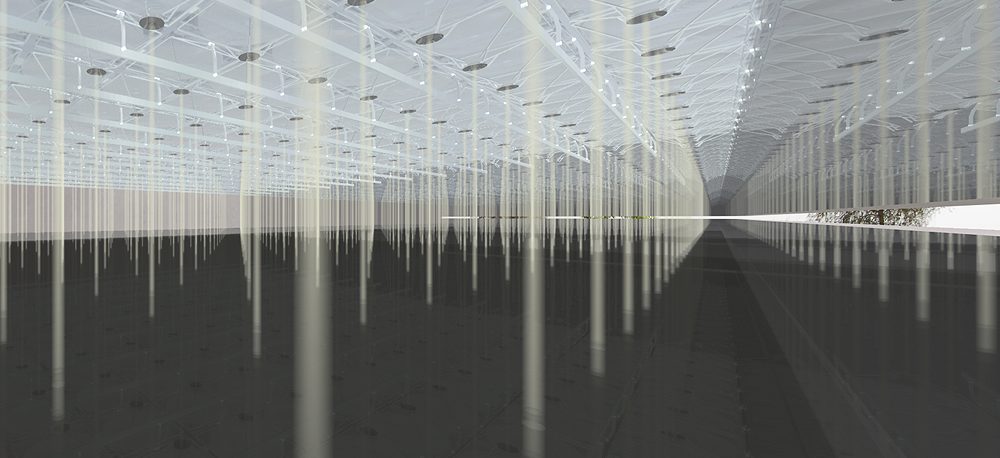

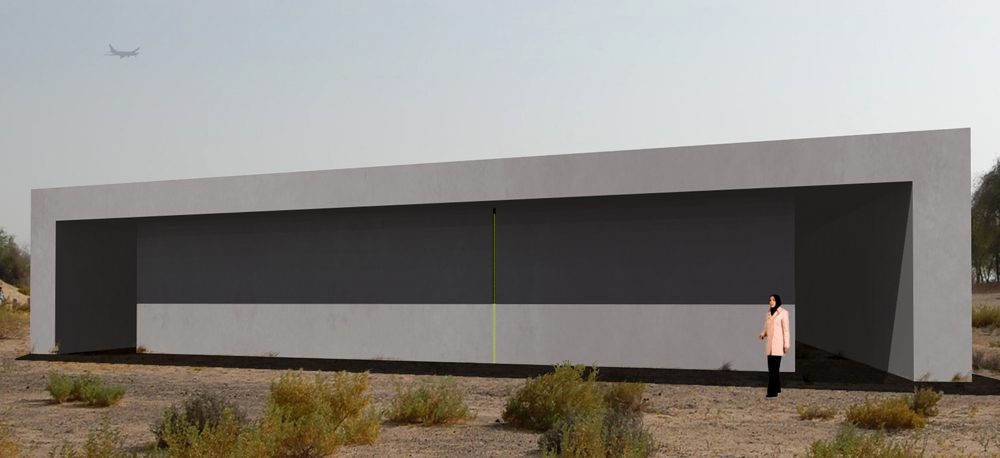

In early 2009, we shared the concept publicly for the first time through an exhibition at the DUCTAC Gallery in Dubai. That year was spent laying the groundwork—selecting sites, developing the first design brief, assembling a jury, and preparing to launch an international open call. We also created a series of “precedent” projects to help communicate the vision. The Ibn Al Haytham Pavilion and the Khorfakkan Necklace, shown above, are among those early explorations.

We launched the first LAGI open call in January 2010. As submissions poured in during the final 24 hours, it became clear that something resonant was taking shape. Hundreds of proposals arrived from more than 40 countries—bold, imaginative, and technically ambitious. The response confirmed that designers around the world were ready to engage with large-scale public artworks capable of generating utility-scale clean energy.

We presented this body of work to Masdar, who generously supported the LAGI 2010 prize and exhibitions at the World Future Energy Summit in January 2011. We are deeply grateful to Masdar, and to Zayed University, whose Provost’s Research Fellowship provided the research platform that enabled LAGI 2012.

Additional early support from the Horne Family Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts made it possible to bring LAGI 2012 to New York City.

This foundational support helped catalyze a global, collaborative effort—one that has since brought together thousands of artists, designers, engineers, students, and community members from more than 60 countries to address one of the defining challenges of our time.

The work continues today thanks to supporters like you, who believe not only in a sustainable future, but in the power of art and design to spark scientific curiosity, civic imagination, and long-term cultural change.

The archives of the Land Art Generator Initiative are housed at the Institute for Art + Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art. Researchers interested in LAGI’s work are encouraged to contact the Museum directly. Nevada Museum of Art