Artist: Binghua Chen

Energy Technologies: organic photovoltaic (OPV)

Annual Capacity: 550 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne.

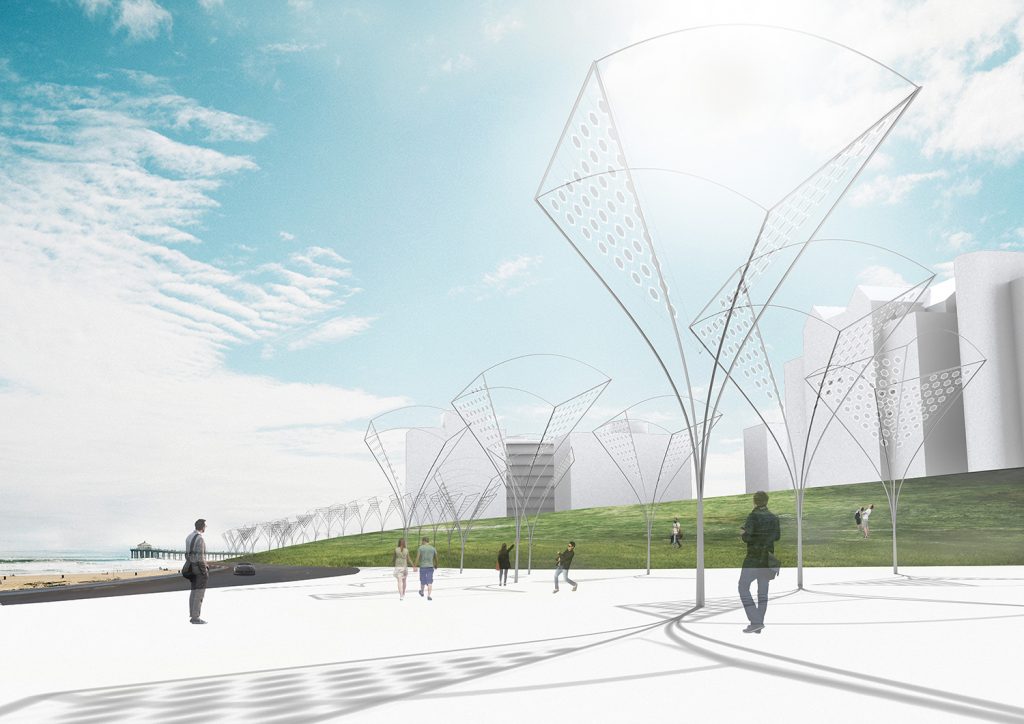

Temple University architecture student Binghua Chen has given solar technology a new lease on life with his innovative EN-Visible Wing land art generator.

From the same class as Kyle Taveira, who entered the LAGI 2018 design competition for Melbourne with Dreamtime, Chen was tasked by Eric Oskey, Associate Professor of Instruction in the Architecture Department, Tyler School of Art at Temple University, with researching the culture of St Kilda Triangle’s Traditional Custodians—the Boonwurrung people. Through his research, he became intrigued with the Eagle, considered a protector god. Careful to balance the abstract and practical, Chen mimicked the wing’s form with his dynamic solar-powered works of art that together produce enough energy to power 110 homes annually.

Eschewing the conventional rooftop solar panel, Chen opted to incorporate flexible organic photovoltaics (OPV) into his design because they are thin, nearly transparent, and lightweight. The solar cells are printed onto modular pieces attached by wires to create two triangular nets that make up the eagle’s wing. This modular piece is then connected to a 7.8-meter-tall by 4.7-meter-wide carbon fiber frame and installed on-site.

In addition to optimizing solar absorption to produce clean energy for the City of Port Phillip as possible, the wings open and close — a flapping movement.

While organic photovoltaics won’t pour out clean energy, the technology has the potential to provide electricity at a lower cost than first- and second-generation solar technologies,” according to the US Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. “Because various absorbers can be used to create colored or transparent OPV devices, this technology is particularly appealing to the building-integrated PV market.” And their flexibility enhances opportunities for creative applications.

For Chen, an architecture student less familiar with various renewable energy technologies than with how a building should function, choosing the appropriate technology for his design was the biggest challenge. One that he handled with aplomb.

Chen arranged his sculptures along the Esplanade leading up to St Kilda Beach in such a way that they can absorb the northern afternoon sun. Further optimizing solar absorption and maximizing electricity output, a light sensor installed on the top of each frame tracks the angle of the sun, prompting a rotor to rotate the frame 30 degrees every hour or 360 degrees in a 12-hour cycle — using its own clean energy. Visually powerful at all times, EN-Visible Wing nonetheless reaches its fullest aesthetic expression at night, after sunset.

“How can people influence the structure?” Chen wonders.

Artist: Binghua Chen

Energy Technologies: organic photovoltaic (OPV)

Annual Capacity: 550 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne.

His response was to equip each frame with touch sensors and LED lights. When visitors brush by the bottom of a carbon fiber frame, the wing lights up — using energy soaked up throughout the day and stored in an underground battery. With this interactive experience, Chen hopes St Kilda visitors will have an educational experience that will promote their understanding of the diverse uses of renewable energy technologies. It’s hard to believe, then, that this is the first time Chen has designed a Land Art Generator artwork—which was why he was interested in Oskey’s class in the first place.

“I wanted to give myself the chance to design something other than housing,” he says of participating in the LAGI 2018 design competition. He wanted to find out “what’s it like doing architecture outside of just buildings.” While the recent graduate is mostly interested in residential design, his experience with LAGI has opened up new possibilities for how he will approach future projects.

Elizabeth Monoian and Robert Ferry, the co-founders and directors of the Land Art Generator Initiative, appreciated the simplicity of Chen’s design, as well as his creative application of OPV technology.

En-Visible Wing is a diaphanous approach to the integration of solar power infrastructure into the city with a light footprint that allows the existing cultural and coastal landscape to continue to be the main visual attraction of the place. While the LAGI competitions are not primarily about university participation (university studios comprise 25% of the entries), we are grateful that professors like Eric Oskey see the value in engaging their students with the design of energy landscapes. It’s critically important that the next generation of designers think naturally and at the very beginning of the design process about the integration of renewable energy into every new work of architecture and landscape architecture.

One of 25 shortlisted designs, EN-Visible Wing represents the maxim “less is more,” says Chen. “Initially when I designed this structure I wanted to keep it as simple as possible. At the same time, I want people to discover the beauty and magic behind this whole panel.”

Tafline Laylin is a freelance communicator and journalist who strives for global environmental and social justice. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, The Atlantic, OZY.com, and a variety of other international publications.