In the ten years that the Land Art Generator Initiative has been holding biennial design competitions, inviting architects, artists, engineers and landscape architects from around the world to submit works of public art that also produce clean energy, the organization has never seen so many local teams shortlisted by the jury.

Despite being strictly anonymous, eight of the 25 teams shortlisted in the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne are from Australia. Here are their cutting-edge designs for St Kilda Triangle—in no particular order.

2000 Murnongs

Artist Team: Azin Emam Pour, Xiao Lin, Qidi Li

Energy Technologies: spring-type piezoelectric

generators, aerostatic flutter (Windbelt™)

Annual capacity: 150MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator Initiative design competition for Melbourne.

All colleagues from ASPECT Studios in Melbourne, Azin Emam pour, Xiao Lin, and Qidi Li took a multi pronged approach to their land art generator design for the City of Port Phillip. Comprised of 2,000 elevated planters populated with indigenous species, including the near-extinct Murnong. The design trio incorporate Windbelts™ on the columns, which generate a small amount of electricity through vibration when the wind blows, while spring-type piezoelectric energy harvesters that connect the planter boxes convert mechanical energy from their weight and motion. At night, the installation transforms into a glowing LED display.

PITCH!

Artist team: Bryan Fan and Shelley Xu

Energy technology: LSC photovoltaic (ClearvuePV®

or similar), lithium ion energy storage

Annual capacity: 100MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator Initiative design competition for Melbourne.

This installation comprises a series of sculptural glass panes that generate about 100 MWh annually for St Kilda Triangle. Local architecture graduates Bryan Fan and Shelley Xu sought to create a “monumental sculpture” that would not only safeguard vistas between The Esplanade and St Kilda Beach in the City of Port Phillip, but frame them. The transparent panels are embedded a light-deflecting compound that redirects ultraviolet and infrared components of natural light to the edge of the glass panels, which are lined with traditional photovoltaic cells that then convert solar energy into electricity. Also equipped with motion sensors and LED lights, the design turns into an interactive light show after dark—enlisting visitors in the quest to beautify St Kilda.

Light Up

Artist Team: Martin Heide, Dean Boothroyd, Mike Rainbow, Jan Talacko, John Bahoric; RMIT architecture students: Bryan Chung, Chea Yuen Yeow Chong, Anna Lee, Amelie Noren

Energy Technologies: flexible mono-crystalline silicon photovoltaic (Sunman eArche SMF 105W poly or similar), wind energy harvesting, Plant-e® microbial fuel cells

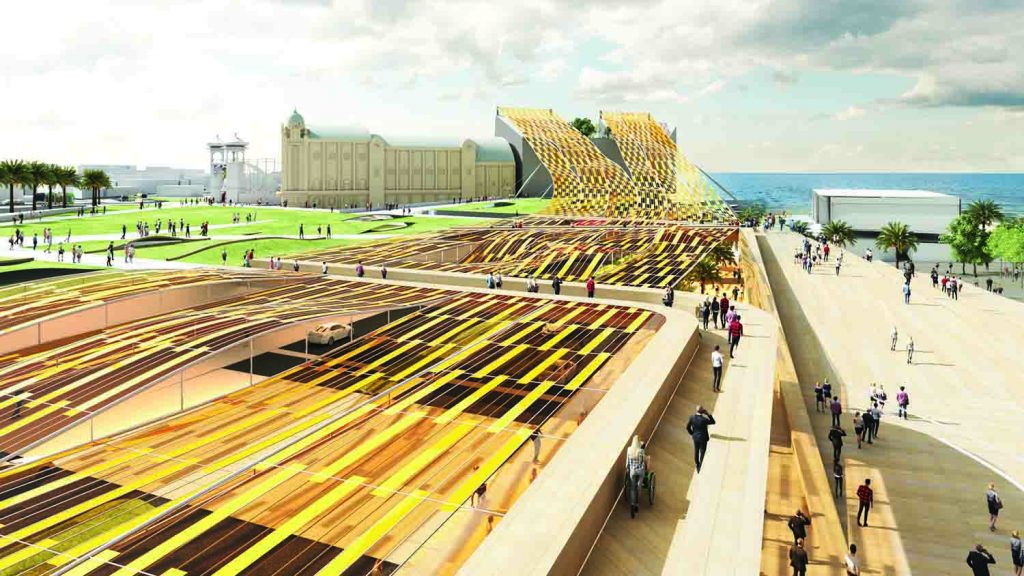

Annual Capacity: 2,220 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator Initiative design competition for Melbourne.

A large team of collaborators led by NH Architecture, including RMIT Architecture students, designed Light Up to use three different clean energy technologies to provide electricity for the City of Port Phillip. The bulk of the energy is derived from 8,600 flexible mono-crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules that form a swooping, undulating canopy that linking various areas of St Kilda to create a unified public park. Wind energy is harvested as it moves the structure, using micro-regenerative dampers at each solar module attachment point and stainless steel cable anchor points. The scheme—conceived as a practical and feasible addition to St Kilda’s existing masterplan—also calls for capturing a small amount of energy from the roots of plants. Using solar energy, plants photosynthesize organic matter, a significant part of which is released into the soil. Electrochemically active micro-organisms break down the organic matter producing electrons, which are transported to the anode of a microbial fuel-cell. The energy rich electrons flow through a load to the cathode to generate electricity 24 hours per day. And then, confronting the intermittency challenge presented by renewables, the design incorporates 107,000 retired lithium-ion batteries that were once used for electric vehicles.

Rotor

Artist Team: Louis Gadd, Aimee Goodwin, Danny Truong

Energy Technology: vertical axis wind turbines

Annual Capacity: 105 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator Initiative design competition for Melbourne.

This design will forever change how you think about wind energy. Comprised of a circular array of custom 1.5 kW Savonius type vertical axis wind turbines that are made from stainless steel and polished to produce a highly reflective surface that acts as a mirror of the landscape, Rotor is an immersive artwork with three horizontal layers. The upper and middle layers are the vertical axis turbines, offset so the posts of the uppermost turbines have an unobstructed connection to the ground. Turbines are not placed on the lowest layer, ensuring visitor safety as they interact with the artwork. Instead, fixed stainless steel panels define entry points, concealing posts from the middle layer of turbines. When wind gusts move through the installation, it causes surrounding foliage to sway in the wind as well—visually communicating the site’s immense energy potential.

Ngargee

Artist Team: Soren Luckins, Ashleigh Adams, George Thompson, Kate Luckins, Alan Pears, Erin Pears, Peter Bennetts, Jasmine Sarin, Elder Arweet Carolyn Briggs, Rae Fairbairn, Dave Stelma

Energy Technologies: amorphous silicon thin-film photovoltaic

Annual Capacity: 400 MWh

A submission to the Land Art Generator Initiative 2018 Competition for Melbourne

Designed in collaboration with First People, Ngargee comprises a series of feather-like forms that represent the feathered wings of Bunjil—a creator deity embodied in the form of an eagle. The feathers that create the installation’s structure are coated with photovoltaic thin-film. Solar cells are also embedded in the pathway through the design to maximize energy production. This energy powers a range of functions, including LED lighting, events, and electric bicycle charging. The surplus energy is transferred to the grid, supporting Melbourne’s vision of a net-zero carbon future. The design’s 11 team members also included in their proposal a misted water feature to provide resource-efficient natural cooling on hotter beach days.

St Kilda Halo

Artist Team: Pete Spence, Hiroe Fujimoto, Sacha Hickinbotham, Michael Richards, Alison Potter, Jason Embley

Energy Technology: silicon photovoltaic thin-film (Sphelar®)

Annual Capacity: 2,000 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator competition for Melbourne

Grimshaw Architects have outdone themselves with an iconic design that mirrors the form of nearby Luna Park’s Scenic Railway rollercoaster. Taking inspiration from the way a forest captures dappled sunlight through the canopy, a team of eight opted to stack an emergent solar technology from Japan. Sphelar, invented and initially developed by Kyosemi, is comprised of tiny spherical balls 1.2 to 1.8 mm in diameter that have electrodes on opposite sides. The tiny silicon balls can be woven into a variety of materials for more efficient energy harvesting than is possible with a flat pane. St Kilda Halo consists of several layers, some receiving more or less light than others, allowing the transparent design to capture energy from any direction. If built, St Kilda Halo could produce 2,000 MWh of energy annually, enough to power up to 400 Australian homes.

The Canopy

Artist Team: Kieran Kartun, Sonni Jeong, Matthew Wang

Energy Technologies: horizontal axis wind turbine, kinetic energy harvesting, concentrator photovoltaic (CPV), concentrated solar-thermal power (CSP), ocean tidal energy.

Annual Capacity: 2,200 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne.

Architecture firm HDR encouraged a few of their employees to enter the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne. Kieran Kartun, Sonni Jeong, and Matthew Wang sought to capture all available energy on site with The Canopy, which comprises a series of sculptural tree-like structures and a modular hexagonal deck. The larger, upper canopies support solar dishes and wind turbines. Beautifying existing technologies like the parabolic trough, which concentrates sunlight onto a fixed point, and horizontal axis wind turbines in the “middle canopy”, the design is utilitarian, interactive, and playful. Kinetic nets amplify the fun factor as visitors interact with them, transforming human kinetic energy into electricity that can be used to charge small electronics.

Rainbow Serpent

Artist Team: Arthur Stefenbergs, Lucian Racovitan, Keith McGeough, Ovidiu Munteanu

Energy Technologies: luminescent solar concentrator (LSC), kinetic energy harvesting

Annual Capacity: 90 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne

Arthur Stefenbergs and Lucian Racovitan created a water-harvesting sculpture that comprises two spiral staircases made entirely out of energy-generating solar glass, and it’s designed to be used. The more people jump and down the structure, the more kinetic energy they produce. Meanwhile, the entire staircase—including the handrails, treads, risers, and columns—is constructed with a luminescent solar concentrator that allows the visible spectrum of light to pass through almost undisrupted. Invisible rays such as ultraviolet and near-infrared light are channeled to the edges where they are converted into electricity with perimeter photovoltaic cells. As people interact with the design, they also learn about the many creative applications capable with renewable energy technologies.