Artist Team: Ruxandra Iancu-Bratosin, Rodrigo Rubio Cuadrado, Alessio Salvatore Verdolino, Alessandro Mattoccia

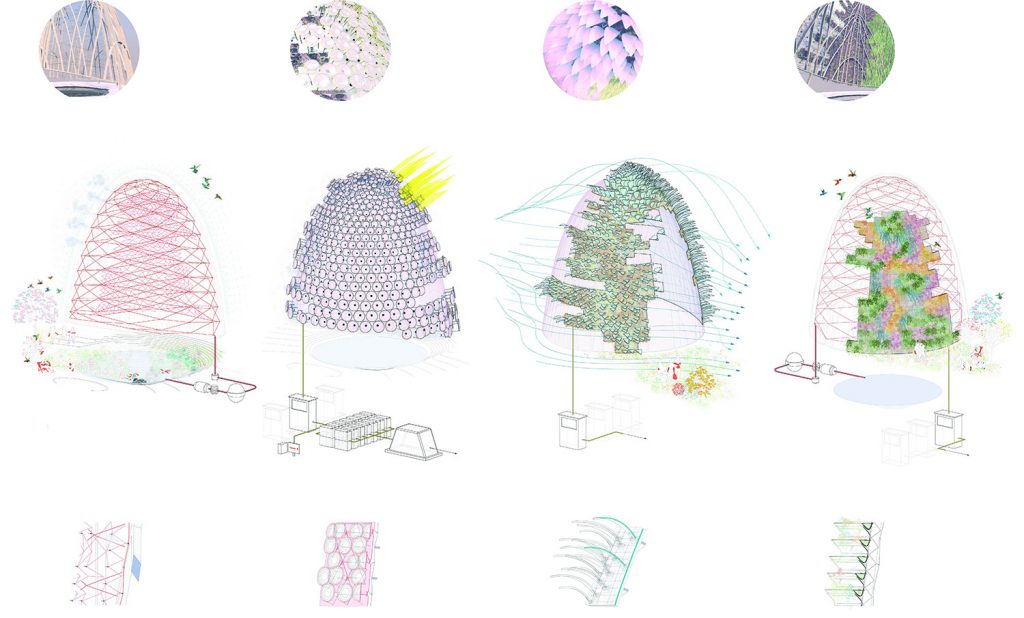

Energy Technologies: concentrated photovoltaic, kinetic wind harvesting, microbial fuel cell

Annual Capacity: 30 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne

Working with the St Kilda Triangle design site situated between city and sea, the architecture team behind Chrysalis decided to set themselves free with a design that prioritizes nature.

This shortlisted design for the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne comprises many parts, including an undulating urban forest in the City of Port Phillip that is populated with a grid of fast-growing Australian white birch trees, three 20-meter-tall (66 foot) energy domes, and an elevated pathway starting at the Bay Trail, crossing over Jacka Blvd, and meandering through the site’s four forest glades.

The glade at the southernmost point of the site consists of an elevated viewpoint prairie looking towards Port Phillip Bay. Ruxandra Iancu-Bratosin, Rodrigo Rubio Cuadrado, Alessio Salvatore Verdolino, and Alessandro Mattoccia—the Madrid-based design team who conceived the large scale artwork—paid careful attention to maintaining views to the bay by proposing to align the trees in NW-SE rows. This, they say, would also facilitate natural wind flow. Meanwhile, the entire constructed topography is designed to steer stormwater runoff to natural pools that collect underneath the energy-generating domes.

Each dome has several layers. The south-facing vegetal skin equipped with plant microbial fuel cells harvests a small amount of energy produced by root microorganisms—a proven technology Iancu-Bratosin says her firm is particularly interested in given their collective focus on sustainability. Translucent leaf-shaped ‘wings’ on the SE-SW side of the domes vibrate when wind passes over them, capturing kinetic energy that is then immediately transferred to underground inverters.

Artist Team: Ruxandra Iancu-Bratosin, Rodrigo Rubio Cuadrado, Alessio Salvatore Verdolino, Alessandro Mattoccia

Energy Technologies: concentrated photovoltaic, kinetic wind harvesting, microbial fuel cell

Annual Capacity: 30 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne

A north-facing solar skin of translucent fabric covered in Fresnel lenses concentrates sunlight onto mono-crystalline photovoltaic cells to harvest solar energy. The concentrating lenses boost solar harvesting efficiency to roughly 40 percent, according to the design team’s artistic narrative. And finally, a water skin complete with water vaporizers and sprinklers uses collected rainwater to not only irrigate the vegetal skin, but also keep the solar cells cool on harsh summer days and create a comfortable microclimate.

Lightweight and modular, the domes comprise a frame of CNC-milled laminated timber, bent to create their vaulted form. This shape was chosen to maximize each dome’s potential to absorb as much of the site’s natural energies as possible. Iancu-Bratosin tells LAGI that they originally conceived of the domes as large barnacles on the site, but ultimately their design was determined by the way they perform in relationship with the natural environment.

“Where do we have the most solar irradiance? How would the airflow move? How can we best use the four cardinal directions?”

Also, though the Chrysalis proposal calls for three domes, Iancu-Bratosin says there could be more or less—depending on the energy needs of any given site—since each self-sustaining unit operates individually. She calls them modular “surprises or kinder eggs that we leave in the forest.”

“In the end, it’s a layer on top of a layer on top of a layer.”

Artist Team: Ruxandra Iancu-Bratosin, Rodrigo Rubio Cuadrado, Alessio Salvatore Verdolino, Alessandro Mattoccia

Energy Technologies: concentrated photovoltaic, kinetic wind harvesting, microbial fuel cell

Annual Capacity: 30 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne

Each node would act as a “cultural catalyzer” that encourages community activities, including themed events and open air art festivals, an aspect of the design designed to meet LAGI’s call for regenerative artworks that are interactive and educational.

And while the design for LAGI 2018 is original, it represents a “collage” of prototypes BASICS architecture has experimented with in the past. For example, they have used energy harvested from plants in other designs, but realized this time they could do more than light up a small LED.

Iancu-Bratosin says they “wanted to create a prototype to demonstrate how far we can take these technologies today, not only the typical way of producing energy, or the typical way of using environmental resources, and hopefully inspire others to come up with even better ideas.”

Elizabeth Monoian and Robert Ferry, LAGI’s founding co-directors, are delighted by the team’s holistic approach to creating a healthy and productive new amenity for both locals and visitors.

We love the seamless combination of playfulness and organic design that creates a mental respite in the heart of the city. In the same way that a deep forest is filled with natural marvels, Chrysalis will remind visitors of the endless wonder of nature.

Artist Team: Ruxandra Iancu-Bratosin, Rodrigo Rubio Cuadrado, Alessio Salvatore Verdolino, Alessandro Mattoccia

Energy Technologies: concentrated photovoltaic, kinetic wind harvesting, microbial fuel cell

Annual Capacity: 30 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne

Since energy is obviously something we are very dependent on, says Iancu-Bratosin, it’s a topic her team finds interesting to explore. They consistently ask themselves: “How can we shift the direction of how and where we source our energy?”

It’s a question we hope an increasing number of people worldwide will consider as an attractive antidote to the carbon-intensive status quo.

Tafline Laylin is a freelance communicator and journalist who strives for global environmental and social justice. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, The Atlantic, OZY.com, and a variety of other international publications.