If you are in search of inspiring clean energy solutions, then you will love the latest book from the Land Art Generator Initiative.

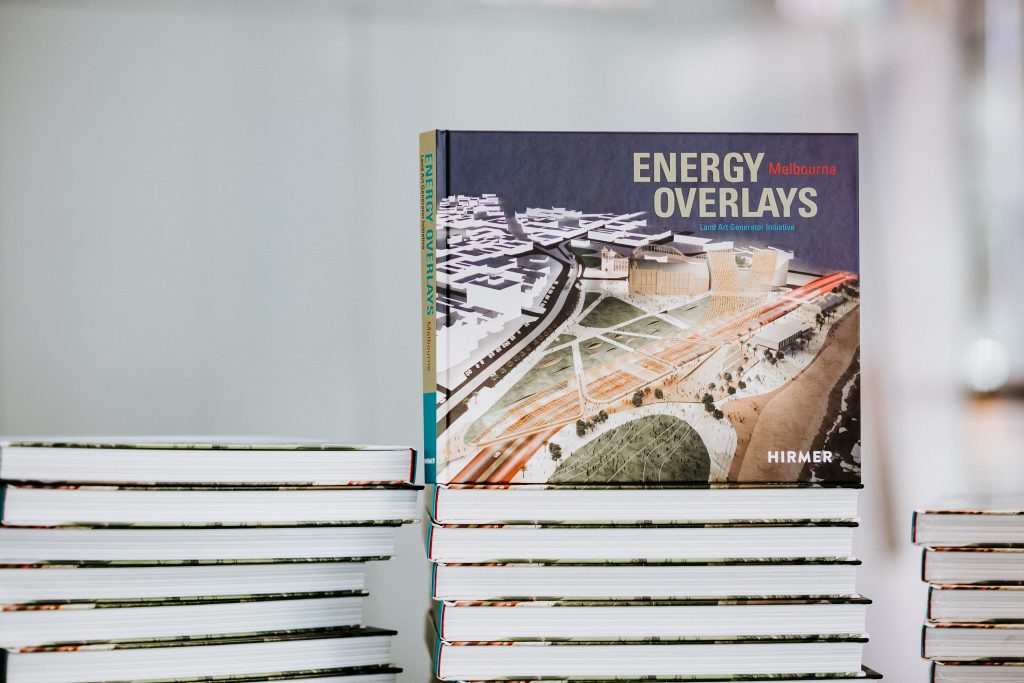

Energy Overlays, now available direct from Hirmer Publishers (or your favorite bookseller including Amazon, University of Chicago Press, and others), is a 240-page hard cover book that provides a glimpse into the beauty of our sustainable future. In addition to descriptions and diagrams of 50 designs from the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne, the publication features a series of essays that untangle paths to the renewable energy revolution so crucial to averting the disasters outlined in the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

“Climate change represents an urgent and potentially irreversible threat to human societies and the planet,” the report’s authors note, urging policymakers to take the necessary strides to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C. But there is still time and there is still hope. The authors themselves note that reaching and sustaining net-zero global anthropogenic CO2 emissions “would halt anthropogenic global warming on multi-decadal timescales.”

The path to net-zero emissions of greenhouse gas emissions entails incorporating a mix of renewable energy technologies, improving the efficiency with which we consume energy, and designing our communities in ways that limits how much energy is required to sustain daily activity. The technologies already exist to make the transition. What we need in order to success is a cultural driver, a motivation for a new and better world that we all can desire to have.

With the LAGI 2018 publication, LAGI co-founders Elizabeth Monoian and Robert Ferry aim to change the message of fear and disaster into one of hope and optimism. “What if we changed the conversation about gloom and doom to one of beauty and cultural transformation?,” they ask in their essay Energy Overlays, Civic Art for a Circular Economy. The goal is to recognize that we are at the beginning of a shift from a culture of consumption and exploitation of nature to a culture of sustainability and stewardship of nature, and that culture and energy have been and will always be intertwined.

“While culture is a reflection of our energy use, the way that we decide to produce and consume energy is also a reflection of our culture. To change one is to change the other. Often solutions to climate change and resource scarcity are framed as scenarios in which the act of energy transition drives cultural shifts (we will need to conserve energy, use less, limit our “lifestyles”), but the key to success may lie in understanding that culture has its own agency. In this equation, culture leads and the energy transition follows.

How we respond to the climate crisis reflects on our true nature, notes Jodi Newcombe, LAGI 2018 project partner and director of Carbon Arts, in her essay The Art of Transition.

“Are we the destructive, selfish species that is doomed to fail,” she asks, “or are we capable of rapid cultural evolution?”

Beautifully laid out by Paul Schifino from Schifino Design, the book demonstrates that rapid evolution is not only possible, but also desirable and exciting.

Each proposal specifies new ways of harvesting energy from available natural resources such as wind, water, or movement. Many of the designs transcend pure energy generation by providing additional services such as soil remediation, rainwater harvesting, or micro climate control. These are the power plants of the future, and they are so clean and safe, people could have a picnic on, in, or next to them. Try that with the local coal plant.

And if you have any doubt that the culture shift is already underway, consider Andrew Dana Hudson’s short story The Lighthouse Keeper, which was inspired by LAGI design competitions. In the author’s world, the future we need is deliciously tangible. All infrastructure is regenerative, functioning in harmony with nature. The story itself comprises part of a new genre that has sprung up around renewable technology, further demonstrating its relevance.

“Within science fiction a new movement seeks to tell fresh stories more relevant to our present crises,” says Hudson of the emerging cli-fi and solarpunk genres. “Much science fiction (including this) is now also climate fiction. For me this means not just discussing the future climate, but implies a contrasting logic: that climate change, not scientific progress, will be the prevailing driver of social transformation in the decades ahead.”

Sometimes in order to understand where we’re going, it helps to look at where we’ve come from. David Helms, Urban Design & Heritage Advisor for the City of Port Phillip, does just that with his essay A History of the St Kilda Foreshore Since 1850. Although he doesn’t delve much into the history of St Kilda’s original custodians, who were far more in tune with genuine sustainability, he explores the site’s legacy as a cultural incubator, providing fresh impetus for a decisive new vision going forward.

Tafline Laylin is a freelance communicator and journalist who strives for global environmental and social justice. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, The Atlantic, OZY.com, and a variety of other international publications.

Related Posts

1 Comment

Add comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

I was looking for something like this, I will surely gonna read that book. Thanks for sharing this article.