Editor’s note: The short story below is included in our latest publication, Energy Overlays, which will be available at all of your usual online and offline booksellers starting on October 11, 2018. The work by Andrew Dana Hudson is a beautiful glimpse into our world a few decades into the future, when we have turned the corner from a culture of consumption to a culture of stewardship of the Earth. Welcome to a world in which we have done the right thing, avoiding the worst effects of climate change, and placing a high social value on those who take care of our systems of survival in a circular economy.

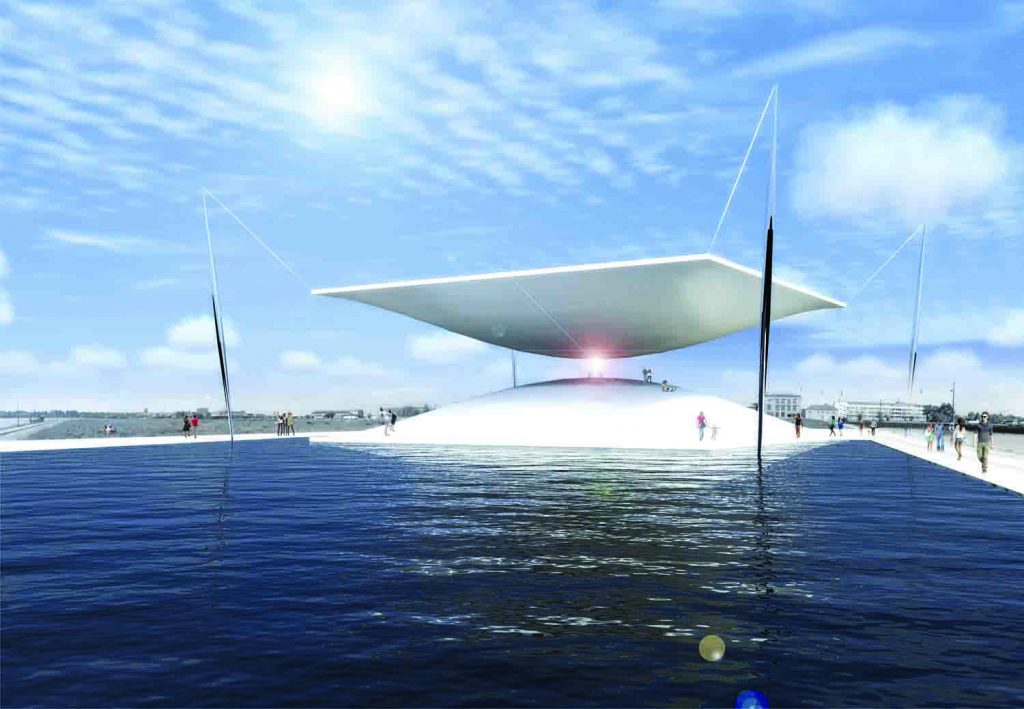

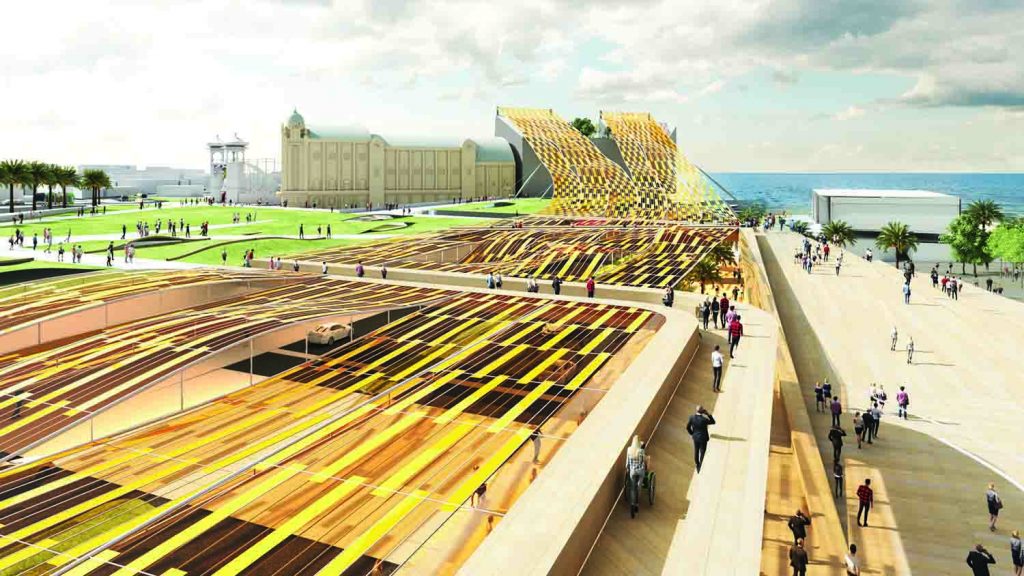

Artist Team: Tim Thikaj

Energy Technologies: wind microturbines

Annual Capacity: 2,016 MWh

A submission to the 2014 Land Art Generator design competition for Copenhagen

The Lighthouse Keeper

by Andrew Dana Hudson

Bast was heading up to the Lighthouse roof, to wipe down the glass, to check the wiring, to clear leaves from the wind pipes, to polish the mirrors, to manage the nesting birds, to oil the hinges, to go through familiar motions that kept his hands busy and his mind unfixed on anything in particular, when his heart stopped working.

Sprawled on the moss floor of the atrium, Bast thought the clawing knot in his chest was just the wind knocked out of him. But then he noticed someone was thumping their palms on his breast. A stranger’s lips blew air into his mouth. They were saving his life. His eyes were fluttering, and the sun seemed shattered by crystal arches and the kaleidoscope tower, engulfing him in spiking color. Yellow and red jackets gathered around, the noon chimes began to play. Amidst the fear and relief, Bast felt impatient with the whole affair. Why don’t you just leave me alone? He thought. I’ve got work to do.

But they didn’t, and the next thing Bast knew he was tucked into his cottage, well-meaning acquaintances bustling to fill his pantry. This was more company than he’d had in a while. The days that followed were the longest he’d spent off his routine in years. He felt like a lump. Confined to bed by a beneficent kit of monitors and regenerative pumps, Bast itched to return to his rounds. He fretted about the scratches and dents ham-fisted substitutes might be leaving on the objects of his care. The installations were durable, but Bast was a perfectionist.

“You wouldn’t let just anyone wipe down the Mona Lisa!” Bast complained.

“The Mona Lisa isn’t bulletproof,” his nurse replied. “And neither are you. Now stop getting worked up!”

No, his carers weren’t having it, and they soon began prodding him to indulge, at long last, the thought of retirement.

“We’ve got some very good candidates,” Terry said, days later. “You put this off too long, mate.”

“I can’t have some intern bungling around,” Bast objected. “I’m right in the middle of renovating the foreshore mosaic. That’s two hundred megawatts a week we’re losing until that’s done.”

“Apprentice,” Terry corrected. “And not from this bed you aren’t.” Terry tapped their long nails on the headboard behind Bast’s back. Bast had argued with the district curator about this before, but this time Terry seemed determined.

“I need to be able to focus,” Bast said. “It’s delicate work.”

“Perfect for young hands.”

“Not ones that don’t know what they’re doing. Look I’ve got notes, you’ve got schematics. When I die someone can figure everything out.”

“Someone, eh?” Terry said. “What happened to the Mona Lisa thing?”

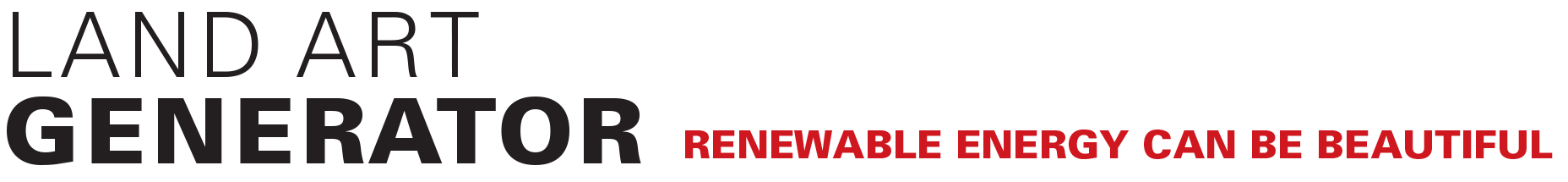

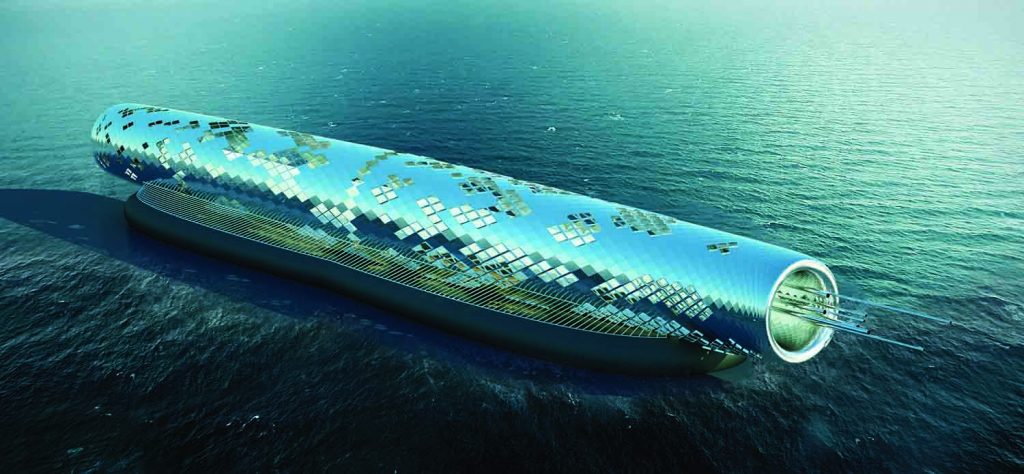

Artist Team: Antonio Maccà

Energy Technology: linear Fresnel reflector

Annual Capacity: 1,100 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator Initiative design competition for Melbourne.

Bast didn’t say anything. Rain smacked horizontal against the windows. First storm of the year and first in a long while. As much as had been done to curtail climate change, the winds still seemed to get harder every season. Bast sighed to think about the leaves and tree branches piling up under fog nets.

Terry sighed, and Bast could see them changing tactics. “Even if that were true—which, ask the curator in Darebin about the right mess they had when their keeper drank himself into the bay—even with perfect notes, people will want to know that their power plants are in good hands. You’re a fixture of the community, Bast! They’ll have my arse if I hand the Lighthouse over to someone without your stamp of approval.”

Bast hated feeling like just another prideful geezer, but the flattery got the better of him. And, as the rain continued the next day and the next, he reluctantly admitted that his heavy lungs were glad to not be trudging through the steamy streets. Might be okay to at least have some help. But who would appreciate St. Kilda’s collection as much as he did?

A week later the nurses unstrapped their machines and pronounced his heart as good as they were going to get it. As he laced up his boots to get back to work, he was so distracted by the to-do list spiraling through his head that he almost forgot the apprentice was coming.

Amelia waited politely outside his front gate, fingering his garden boxes, which looked limp after the week of storms. She was stocky where he was thin, tan where he burned, wore glasses but no headphones. Bast tried to imagine what he could possibly have in common with this child.

“Alright then, I’ve got a lot to do,” Bast said by way of greeting. “So just you watch, and do as I say, and save your questions a few days ‘til after I’ve caught up.”

“You need storm nets for these waratahs,” Amelia said, trying to straighten one of the flowers. “They tighten closed when the wind picks up. I can bring some if you like.”

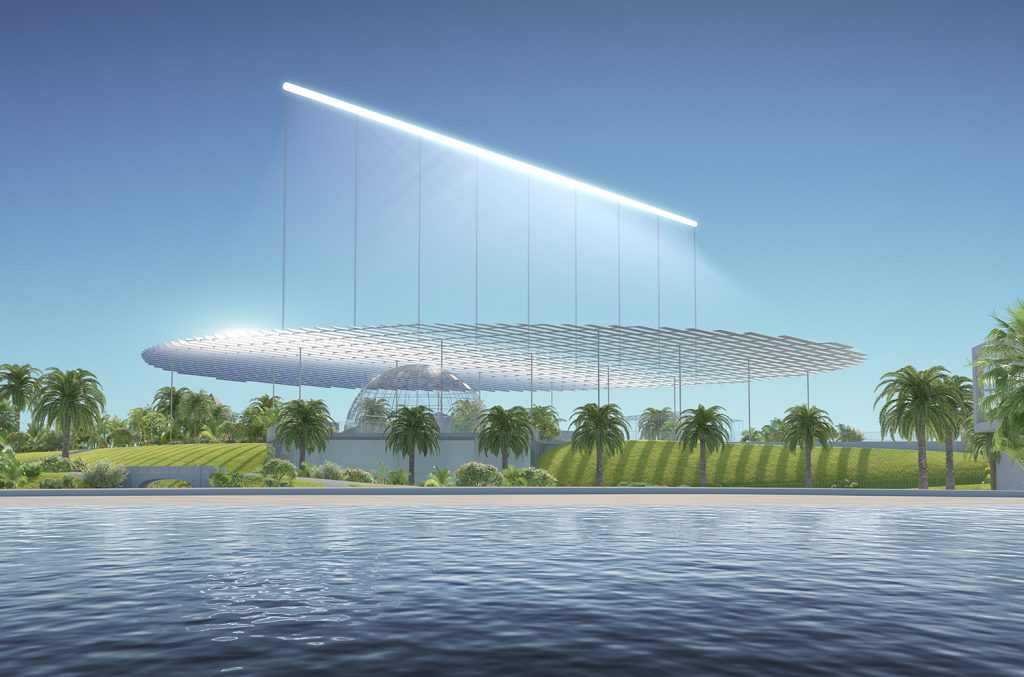

Artist Team: Christopher Sjoberg and Ryo Saito

Energy Technologies: Aerostatic Flutter Wind Harvesting (WindBelt™)

Water Harvesting Technologies: fog harvesting

Annual Capacity: 70 MWh (used on site) and 112 million liters of drinking water

A submission to the 2016 Land Art Generator design competition for Santa Monica

Bast harrumphed and started walking down Peel to Chapel. Here people lounged in the street grass, waiting for the tram or the Sandringham train. It was already hot, and the busy tram was late, so a few commuters took calls in the shade of the Windsor power plant—a great trapezoidal shard lifted over the train station by supports painted like beanstalks. Black photovoltaics, a decade young, covered the top. The underside was a technicolor cloudscape, sparkling with LEDs.

Bast pulled rags and cleaner from a hidden closet, then eyed the beanstalk. The nurses hadn’t said no ladders, but he was already winded from the short walk. He handed the rag to Amelia.

“Soft circles, six per spray,” he said, demonstrating the technique. “You’ll want to peel off the birdshit, otherwise it’ll streak. Have a go, eh?”

Bast sent Amelia up through a locked panel in the clouds. Then he found a perch on Chapel Street and sat down to watch her wash a month’s worth of grime off the photovoltaics. A little dirt didn’t decrease their output, but Bast loved seeing his reflection in clean, shiny solar. He half-hoped to see signs of distress, to hear excuses or stupid questions. But Amelia scrubbed gamely away, and he felt a pang of shame at his standoffishness.

“How old are you, anyway?” Bast called.

“Nineteen last Friday,” Amelia said. “How old are you?”

“Stopped counting,” Bast said. Then, feeling he should at least offer advice if he wasn’t helping, added: “You do this work, I suggest you do the same. No sense in marking anniversaries like, ‘thirty years trimming hedges, twenty years tightening screws.’”

Amelia seemed to mull this over. She climbed down, and Bast had Amelia watch the underside for dead LEDs while he logged into the dashboard. The trapezoid had been running a smidge low in his absence, but still provided a good portion of the neighborhood’s power.

They worked their way down towards the bay, stopping to tidy up the piezoelectric jungle gym at Alma Park and the botanical garden’s meter-wide refraction globes, which rested like raindrops in giant, aluminum lotus flowers. Each installation was unique, and so required a unique regime of monthly care, which existed now for Bast as muscle memory. Usually he went about the work automatically, his mind logging parts that were showing wear and thinking of the craftspeople he’d need to seek out to fix them. It was oddly exhausting to now sit back and explain what his hands did automatically.

It was already noon when they rounded on the marina, and the chimes of the Lighthouse drifted to them down the parade. Bast wanted to tell himself that Amelia’s presence slowed him down, but truth was he was the slow one. His breath went short after a few stairs, and his back ached from too many days in bed. He eyed the glass tower poking over the low rooftops, and felt his heart start to thump louder.

“Oi, fancy some lunch?” he asked. “Chimes don’t sound too off. We can hit the big boy in the arvo.”

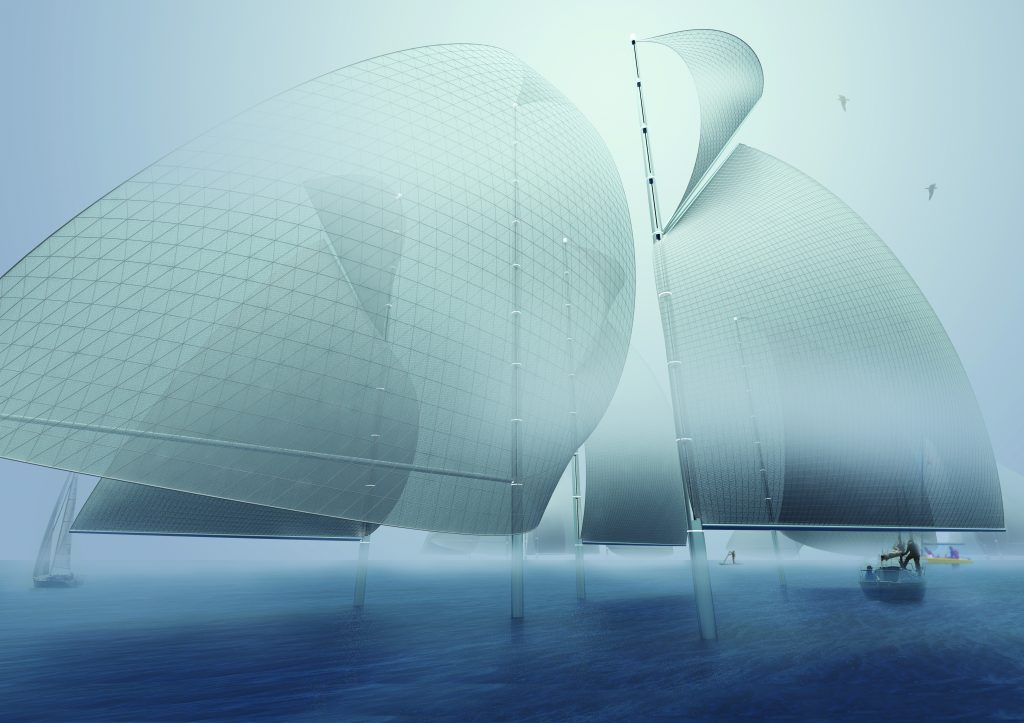

Artist Team: Kyle Taveira

Energy Technology: triboelectric energy harvester fabric and piezoelectric stack actuators

Annual Capacity: 100 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator Initiative design competition for Melbourne

Amelia looked surprised but nodded vigorously, so they walked across the street to a cafe, squeezing past sweaty cyclists to order waffles and smashed avocado on toast. Bast knew everyone, but he was surprised to see the barista wave at Amelia, who popped off to chat.

“Where are you from, anyway?” Bast asked when she returned. Terry had gushed to him over her interview, but he didn’t remember much else.

“Down Bentleigh East,” Amelia said, shaking pepper onto her toast. “But I spent most of my break days in St. Kilda. Love the beach, you know. Four years, life saving certified!”

Bast swallowed down his bite of waffle. He remembered the yellow and red jackets. “Were you there? At the Lighthouse, I mean. When my heart…”

Amelia looked guilty, but he wasn’t sure what for. “No. I heard about it though. But I’d already been applying to the curator for months, honest!”

It occurred to Bast that, as he’d been keeper in St. Kilda for most of his life, his taking ill might have meant a scramble of people keen to replace him. He wasn’t surprised; the keeper job paid good wages, guaranteed forever by the Lighthouse charter, and the work was there as long as he wanted it. It wasn’t glamorous, but in the gentle long tail at the end of industrial expansion, Bast believed that maintenance was the best and realest work around.

“Ay, no worries. Just, see if you still want the gig after this week, right?” Suddenly Bast felt very tired. He felt the Lighthouse in the distance. “Actually, let’s knock off for the day. That okay with you?”

“Uh, yes,” Amelia said, and they washed their dishes and left.

The next week they swept grass clippings off the solar hills of Albert Park golf course, and checked for leaks in each solar balloon that hovered over Albert Park Lake. Then they gave a proper tune up to the wind turbine that mirrored the 600-year-old Corroboree Tree. Amelia learned fast, Bast had to admit, and she knew when to check with him about a loose screw or bit of rust. Soon he gave up his ban on questions and let her pry from him the history of each artwork and its service to the city.

The week after that he took her down towards Elwood, where a few blocks had taken on the spirit of Venice in anticipation of rising seas. They snagged a share-boat at Milton and Broadway and paddled down the extended canals to Elster Creek, and over to the Bay. There a Korean sculptor was building a dike that would power a desalination plant with the creeping pressure of the tides. Each year the municipal curators found new spots for artists to set up power-giving installations, letting the roots of civilization erupt into beautiful view.

“You’re avoiding the Lighthouse, aren’t you?” Amelia said the next week.

“Lighten off,” Bast grumbled. “I’m working my way up to it.”

Artist Team: Santiago Muros Cortés

Energy Technologies: concentrated solar power (thermal beam-down tower with heliostats)

Annual Capacity: 6,000 MWh

First Place winner of the 2014 Land Art Generator design competition for Copenhagen competition

At the end of the month, he had Amelia collect their equipment from around the neighborhood and lug it to his house for a cleaning. It had been a four-season day that settled on sweltering summer, but they set up their buckets on his front patio anyway. Tool care was his favorite Friday night, set to beer and music. As much as he longed for the solitude of this ritual, however, it didn’t feel right to box Amelia out of this part of the job.

“So where are all your cats?” Amelia asked.

“No cats. I don’t like cats.” Bast knew where this was going.

“You’re called ‘Bast,’ and you don’t have cats?” Amelia sounded genuinely shocked.

“It’s just a name,” Bast said. “Doesn’t mean anything. What does your name mean?”

“Industrious,” Amelia said promptly.

Bast harrumphed, but handed her a tinny.

“Why don’t you like cats?” Amelia asked.

“Why don’t you want to go to school?” Bast deflected.

“I am going to school,” she said. “Apprenticeship, right? I’m supposed to learn from you!”

“I mean to learn something proper. History or painting or cooking. Something that will make you sound smart at parties.”

“I already sound smart at parties,” Amelia said. And it was true: she had a quick wit when she wanted, Bast had learned.

“Well,” Bast considered, “the parties are easier at your age. Wait until you’re me, and Terry drags you to a fancy reception with ambassadors and visiting mayors and all, and you’ve spent your life going round and round the same ten kilometers. Hard to feel clever then, let me tell ya.”

Amelia waved her beer at the neighborhood around his garden. “You crack up the latte guy every day. Everyone knows you! Who cares what some foreigner thinks?”

“Ta, yeah, not me, I suppose,” he said. “Just want you to know what you’re getting into.”

They washed and oiled the tools. Like the installations he tended, many of them were one-of-a-kind, fabbed for a particular task on a particular sculpture. Bast knew each object by heart: a deep, ungeneralizable knowledge that came only through endless hours of handling and use. He knew which extra-long screwdriver he’d need to open the angel at Victoria Gardens, and which specially curved shears best trimmed the topiary figures dancing around the airwells at Fawkner Park. He knew how much force each scraper needed to dig the most dirt out from the seams between solar panels. He knew which parts of each blade dulled first, and how frayed a mop could get before it stopped being useful on textured glass over crystalline silicon.

After a month of pointing and directing, it felt good to sit and let his hands move through the familiar rhymes, honed over years: inspect, wipe, wash, dry, inspect, oil, wipe, stow. Amelia watched, amazed, as Bast’s rags danced over the tools in efficient swipes. They finished as the sun went down. Bast got them more beers. As he handed Amelia a can, the streetlights pulsed on.

“You ever notice that those things look a bit brighter on Fridays than they do on Mondays?” Amelia mused. Bast was pleased.

“Well, tonight they are brighter,” he said. “The infrared solar cells around here make a bit of charge just from the moonlight, the stars, the heat of the Earth—long as they’re clean and tuned up. At night the grid switches to the big battery on Coode Island, so the local solars dump their juice into the nearby streetlights. But month by month the panels pick up a nice layer of grime, and the lights dim, just a bit. Then a keeper makes their rounds and…pop! Bright as you please.”

“That was us?” Amelia said.

“Well, we’re the keepers around here, so,” Bast said, “that was us.”

Amelia pondered this in silence for a few minutes. Then she spoke up. “Can I ask you a question?”

“Alright, have a go.”

“How come you never married?” she asked. It wasn’t the question Bast expected.

“I was married,” he said. “Early days of this job. Nice girl from Camberwell.”

“What happened?”

“She moved to Brisbane. When we hitched up, she said she wanted to stay here, but then she didn’t. Still surprised she picked Brisbane though, of all places.”

“You didn’t go after her?” Amelia asked. Then, sarcastic: “In movies you’re supposed to go after her.”

“Well, I had the Lighthouse.” Bast swigged his beer. “Actually, she’s the one who called me Bast. Said I was like a cat. Bred to hang around, keep the rats off, but not much else. Couldn’t train me, she said, bit of a joke. I kind of liked the name, so I kept it. Fewer people had heard of me that way. Better than being sad Eddie whose wife ran off.”

“Bast is a sun deity, too. I looked it up,” Amelia said. “That’s something you could use at a party.”

“You know, I just might.”

“So can we do the Lighthouse next week?” Amelia asked.

Bast crumpled his beer can, binned it in the recycling. “I guess we better,” he said.

Artist Team: Jaesik Lim, Ahyoung Lee, Sunpil Choi, Dohyoung Kim, Hoeyoung Jung, Jaeyeol Kim, Hansaem Kim (Heerim Architects & Planners)

Energy Technologies: organic photovoltaic (OPV), kinetic harvesting (piezoelectric)

Annual Capacity: 4,229 MWh

A submission to the 2014 Land Art Generator design competition for Copenhagen

Monday morning they did the carbon capture prayer wheels at the Balaclava Station bridge, and the solar Serra on the lawn at Labassa mansion. Then they walked up towards Jacka Boulevard, past the amusement park with its pressed-wooden rides, and the ancient theater.

The Lighthouse was clear and iridescent, like a cathedral built at the World’s Fair. Despite being made of transparent solar panels, it was, still, recognizably a lighthouse. A cylindrical tower, a hundred meters tall, rose from one corner of an open building Bast called ‘the barn.’ There park-goers and tourists wandered in to see the exhibits, chew sack lunches, or meet friends before heading to the beach. Atop the barn was a vast fog net, a sail that pulled fresh water from the wet bay wind.

Bast had been made keeper when it was built back in the 20s, and yet, forty years on, he still found new things to admire. For a few years he had traced its swooping lines, then noted how the prism pillars pulled rainbow colors from the light. He watched the water trickle down from the sail and drip from the ceiling onto the mossy earth. He spent a decade listening to the chimes—ethereal tones, six times a day. They reminded him sometimes of a Tibetan singing bowl, sometimes of beer bottles clinking in the wind.

Then, for a long time, he watched the people. Watched how they kicked off their shoes to ground themselves before touching the pillars. How they opened their mouths to catch droplets, or found a dry spot to sit and read, or napped while charging their phones at educational outlets. He waited for the moment when they looked up to take in the electric magic that turned sunlight into music and air conditioning and tram travel.

Now he looked at the Lighthouse with something new: trepidation. His chest tensed at the memory, and he thought of how close he’d happened to brush against death in this place. But then Bast glanced at Amelia and realized she’d probably been looking at this place for years, too. He’d seen the Lighthouse built, but she’d grown up with it. He wondered what she’d noticed. Then Amelia, right on cue, pointed at the far corner.

“When I was a tot my oldies used to drop me off there during farmer’s market,” she said. “I’d do drawings of the prism colors, try to hand them out to people. I guess I was kinda the unofficial Sunday tour guide. You know, sometimes the chimes lined up with church bells from up Acland Street, and everyone would just stop and let the whole place vibrate like a tuning fork.”

Bast hardly ever came to the Lighthouse on Sundays, when it was busiest.

“I like to think we built some good things, my generation,” Bast said. “Not me, of course. But I do my part. Don’t want it to become some dusty ruin, like I grew up in. Just, sometimes I worry that young folks are gonna see this stuff as in their way.”

Artist Team: Martin Heide, Dean Boothroyd, Emily Von Moger, David Allouf, Takasumi Inoue, Liam Oxlade, Michael Strack, Richard Le; Mike Rainbow, Jan Talacko; John Bahoric; Bryan Chung, Chea Yuen Yeow Chong, Anna Lee, Amelie Noren

Energy Technologies: flexible mono-crystalline silicon photovoltaic, wind energy harvesting, microbial fuel cells

Annual Capacity: 2,220 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator design competition for Melbourne

“Well, not me. I like it.” Amelia shrugged. “But that’s why we take care of things, eh? So the next folks can have a choice about it. They can tear it down, build their own thing. But if we do this right, they can still keep it, if they want.”

Suddenly Bast desperately wanted Amelia to take the job. He wanted to give her the beauty he’d seen in the Lighthouse, and the dozens of other works of public whimsy that gifted the city with water and power. He unlocked the ladder and waved Amelia on.

“Up we go,” Bast said.

They climbed into the tower. Amelia first, then Bast. Once in the tower the chatter of the barn faded, and Bast was left with no sound but the humming of the wind, the patter of their climb, and the engulfing drumbeat of his heart. He gripped each rung tight, eyes on Amelia’s shoes. He took long, deliberate breaths. He tried not to think about the illumination that had pierced his half-conscious eyes, that had seemed to want to pull him up.

It was a bright, noon day, and the sunlight swam straight down into the cylinder. What didn’t charge the solar panels was bounced into the barn prisms by relay mirrors. The whole apparatus shifted with the swaying of the sail, and so the interior of the barn danced with rainbows and fairy lights. But inside the tower itself, where few but the keeper got to see, the sun was like fireworks in a funhouse. Against his better judgement, Bast closed his eyes and climbed by feel. Then Amelia’s strong hand grabbed his arm and pulled him out onto the barn’s glass roof. A chilly antarctic breeze whipped at their hair. Amelia was grinning, and waved at a little girl, staring up at them from the barn below.

“Tried to sneak up here once,” she said. “But me mum wouldn’t let me pry the lock. Suppose you’d’ve had to fix that.”

“All in a day’s work,” Bast said. “Come on.”

Together they wiped down the glass and checked the wiring. They cleared leaves from the wind pipes that made the Lighthouse sing and polished the tower’s mirrors. They oiled the hinges of the sail and gently shooed away nesting birds. It wasn’t a lot to do, but it was work that needed doing. Renewable didn’t mean free. Someone had to be there to do the renewing.

Artist Team: Abdolaziz Khalili, Puya Kalili, Laleh Javaheri, Iman Khalili, Kathy Kiany

Energy Technologies: Photovoltaic Panels

Water Harvesting Technologies: Electromagnetic Desalination

Annual Capacity: 10,000 MWh to generate 4.5 billion liters of drinking water

A submission to the 2016 Land Art Generator design competition for Santa Monica

The work was less automatic with Amelia there, but Bast found a different kind of rhythm in his explanations. He talked her through walking on the slanted glass, which swaths got dirty first, how to spot a tile that might come loose in a few weeks. Knowledge that was hard to capture in schematics.

When they finished, Amelia began to descend to the barn. But Bast stopped her.

“You wanna see the top, don’t ya?” he said, and he showed her the second ladder, rising to the lantern room.

The climb up was long and dizzy-making; Bast didn’t make it often. More than once he had to stop and lock his arms in the ladder to catch his breath. When he reached the lantern room, Amelia was leaning out to peer at the Melbourne skyline.

“This never gets old, does it?” she asked.

“Oh, it does,” he said. “But you can get old with it.”

Down below the wind pipes opened, and the pulsing tone of chimes bubbled up from the barn. At the center of the lantern room a beacon the size of a jackfruit flashed out at the bay—a nod to the works that communities build in service to a bigger world. Around them the city crawled with trams and trains, bikes and electric skateboards. Each roof burst with greenery, or glinted with postage-stamps of black solar, drinking the sun. Could this last forever? Bast wondered. He couldn’t think why not. Amelia moved back to the ladder, looked at him.

“You can stay here a while, if you like,” she said. “I can finish the work.”

Artist Team: Pete Spence, Hiroe Fujimoto, Sacha Hickinbotham, Michael Richards, Alison Potter, Jason Embley (Grimshaw Architects)

Energy Technology: silicon photovoltaic thin-film (Sphelar®)

Annual Capacity: 2000 MWh

A submission to the 2018 Land Art Generator Initiative design competition for Melbourne.

Author’s Note on The Genre

The Lighthouse Keeper is a science fiction story inspired by the LAGI design competitions. Within sci-fi, a new movement seeks to tell fresh stories more relevant to our present crises. Much science fiction (including this) is now also climate fiction. For me this means not just discussing the future climate, but implies a contrasting logic: that climate change, not scientific progress, will be the prevailing driver of social transformation in the decades ahead.

Given the dire predictions made by scientists, one would expect cli-fi to be grim and pessimistic, and plenty is. However, as this story demonstrates, it doesn’t have to be! Another new subgenre, solarpunk, seeks to offer more hopeful visions of the future—or at least a sense of what trying to clean up this mess might look like. Where cyberpunk speculated about computation and other technologies of abstraction, solarpunk now considers the implications of abundant renewable energy and technologies that improve our relationships with the living world.

All of this is in flux, just like the fate of our planet. Unlike Bast’s world, which feels governed by pleasant and thoughtful routines, our world is up for grabs. Thus our stories should be useful. Our words and deeds matter a great deal in this moment—particularly the speed with which we imagine, organize and execute major shifts in the infrastructure of civilization. Let us hope that on the other side of that great work, our grandchildren might know a world of beauty, sustainability, and care.

Author’s Bio

Andrew Dana Hudson is an award-winning speculative fiction writer. He studies at Arizona State University in the School of Sustainability and is a fellow in the Center for Science and the Imagination’s Imaginary College. His fiction seeks to envision the lived experiences just around the corner in our climate-changed world, and the struggle to make good choices that can navigate our civilization through the sustainability crisis. His research explores how scholars, designers, and creatives can collaborate to tell useful stories about our post-normal world.

Andrew has previously worked as a journalist and as a political consultant. His nonfiction writing has appeared in Slate and The Chronicle of Higher Education. He also serves as an associate editor at Holum Press, which publishes Oasis, a Phoenix-based journal of anti-capitalist thought.