The winners of the LAGI Willimantic design competition in Connecticut credit, in large measure, their engagement with the local community for developing their winning proposal.

Laura Pirie from Pirie Associates describes how her team spent over 20 hours talking to members of the community to better understand their needs and vision for a riverfront placemaking project initiated by the Willimantic Whitewater Partnership (WWP). The non-profit organization has spent more than a decade transforming a 3.4-acre downtown brownfield site along the Willimantic river into a new recreational facility—but eventually they realized they couldn’t do it alone.

In order to advance their goals, WWP involved the Institute for Sustainable Energy (ISE) at Eastern Connecticut State University (ECSU) and the State of Connecticut’s Department of Economic and Community Development (DECD). In turn, Kristina Newman-Scott, Director of Culture in the Office of the Arts & Historic Preservation at DECD, brought on board Elizabeth Monoian and Robert Ferry with the Land Art Generator Initiative. Pirie calls this collaboration a “powerhouse of stakeholders.”

Together they launched the LAGI Willimantic design competition to create what Pirie says is more than just a recreational park facility. Instead, she says, the project “brings hope and development and a focus to the future of Willimantic.”

Why does this matter? Until recently, Willimantic—which is part of Windham—has been struggling to reinvent itself since the textile industry moved south with the American Thread Company’s 1985 closure. With its main revenue source gone, the community has gone through dark times. In 2002, the Hartford Courant newspaper reported an uptick in heroin use. Still, while the past shapes our present, it certainly doesn’t define our future. With this in mind, Willimantic has taken several progressive steps to ensure a creative new future for this post-industrial community—and developing an energy-generating public art is one of them.

LAGI co-founders, Elizabeth Monoian and Robert Ferry, say they are delighted that the Willimantic community has embraced the idea of regenerative infrastructure.

“The project shows how in the 21st century we are embracing a new paradigm for development that weaves together multiple systems in one place: public art and culture, sustainable energy generation, recreational riverfront park for people, educational venue, river conservation, and habitat protection. An interdisciplinary design approach and a shared use of land can lead to outcomes that are greater than the sum of their parts to create lasting social and environmental value. This new kind of place can be a catalyst for regional growth and a model for surrounding communities.”

After meeting residents over breakfast, at the library, and even talking to Santa at the mall before Christmas, Pirie says, “…it’s in hearing those voices that we could actually then act on behalf of the community to create a solution that brought not only this general idea of healing to the site, but their specific design for healing and for community.”

Their resulting proposal, Rio Iluminado, has two main purposes, according to Pirie Associates. One, “to connect people to the river and to each other.” And then, on a more practical level, “to generate energy in a demonstrative and beautiful way.”

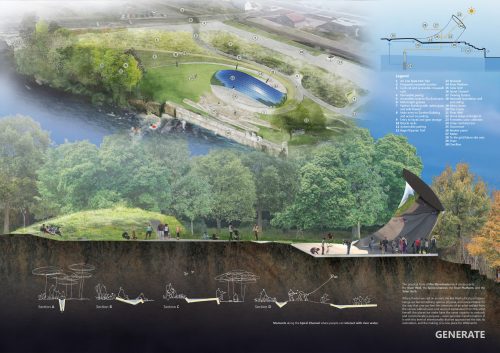

Pirie Associates says their design has four physical components: the River Well, the Spiral Channel, the River Platform, and the Solar Arch.

The River Well draws underground water through a submersible well pump that is powered by solar energy. Located in a proposed Tree Copse located on a part of the site that has never before been developed, this aspect of the design represents healing decades of industrial use.

The Spiral Channel takes the water from the River Well to the River Platform, according to Pirie Associates. Those people who aren’t able for whatever reason to engage with the whitewater or surrounding trails can still connect with the river through this channel, which encourages interaction — whether it’s splashing around or sitting on the low concrete edges.

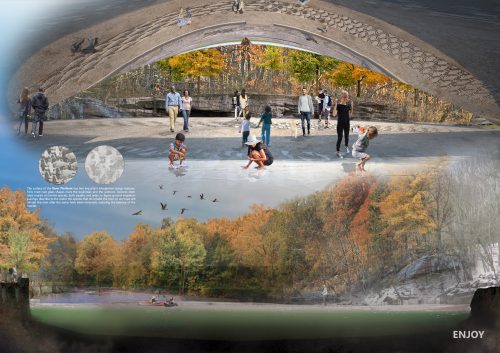

The Spiral Channel travels to a 3400-square-foot concrete slab, the River Platform. Here visitors can learn about the site’s riparian species, and observe how much water flows from the River Well (depending in part on how much solar energy is being generated). In winter, this platform can be used to create an ice-skating surface—making the park fun and accessible year-round.

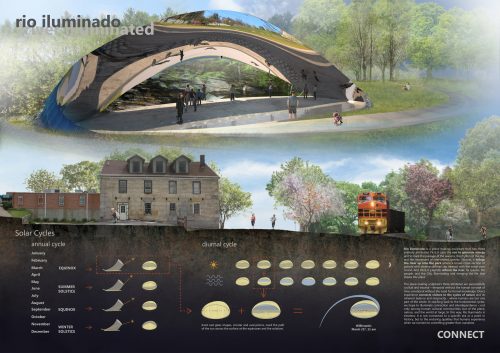

Finally, a splashy centerpiece: the Solar Arch. Covered in a 900 sq. ft. solar array, this shimmering work of public art is capable of producing around 25.5 MWh of clean energy annually. “The surface is shaped specifically to reflect, overlay, and merge the river, the River Platform, the people, the site, and downtown beyond,” writes Pirie Associates.

“The purpose of the reflective surface is poetic and playful: it’s meant to simultaneously capture the river, the site activities, and the city in one “parallaxical” composition, superimposing and joining the LIFE of the area into one active, changing mural of connection.”

Now in the midst of the project’s second phase, the Rio Iluminado team is currently developing their design for production. Pending funding, the third phase would see the project’s ultimate construction. For more detailed information about the design process, head over to Pirie Associates.

Tafline Laylin is a freelance communicator and journalist who strives for global environmental and social justice. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, The Atlantic, OZY.com, and a variety of other international publications.

Related Posts

2 Comments

Add comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Place-making is a new approach to urban planning—one that responds to the true needs of communities and creates environments that are more social, vibrant, and active. Through our events and programs, we help municipalities and community organizations build interest in their town centers, create local consensus, and formulate strategies for moving forward.

[…] With wavy forms that enhance the overall aesthetics, the solar arrays are also functional. Energy absorbed throughout the day is stored for nighttime use, powering 15 LED street lights that not only make the site safer at night, but also usable. A place that was once feared has become a beacon of light in both the physical and metaphorical sense. It's an excellent example of the kind of collaborative effort and integrated design required for successful creative placemaking. […]