How to Plan Inclusive Renewable Energy Infrastructure for Communities

Involving the Community from an Aesthetic, Social, and Civic Perspective

If we stand a chance at avoiding the worst impacts of climate change, it is important that the public have positive associations with renewable energy at the neighborhood level. Distributed energy resources in cities (rooftop and community solar) are more resilient and less expensive than large remote centralized power plants. Building energy infrastructure in our cities conserves natural landscapes and offers opportunities to improve social equity and quality of life. In order to reach the thousands of gigawatts of installed renewable energy capacity required for the global energy transformation, we will need to look beyond rural landscapes and toward site opportunities that are nearby or within residential and commercial districts, where the standards of design for public space are critically important.

Stemming the rising tide of climate change will also mean that more of us will become energy developers, participating in energy projects in come capacity beyond “energy consumer,” even if just to install PV modules on our roofs. Being an energy developer (or prosumer) means that you are helping to bring some kind of renewable energy project to your community. More people are coming together, pooling their resources to assess sites, plan, finance, and implement new energy projects in their neighborhoods.

As we shift energy deployment from greenfields and deserts and bring it into our cities, developers will be looking for new models that can expand the range of potential sites. Fencing off empty urban lots and converting them to gravel fields with ground mounted PV modules will only work in certain situations. Insisting on bringing the utility engineering approach into cities risks giving solar a bad name. The temptation will be there to install solar projects in neighborhoods with less expensive real estate and to get projects permitted with a minimum of community engagement to cut costs. But we can’t afford to repeat the urban planning mistakes of previous infrastructure projects. And we don’t need to. When you step back and look at the big picture of distributed solar deployment in cities, there is great opportunity.

Incorporating community and stakeholder engagement into the energy developer business model can provide lasting benefits throughout the life cycle of projects. This could take form in a variety of ways.

At the minimal end of the spectrum energy developers can hold public information sessions and facilitated workshops that introduce neighbors to the early stage planning process, and that solicit constructive feedback on key decisions that will be made in the next stage of project development.

Developers who can see the bigger picture will choose to engage the community through a co-design (or participatory design) approach to the development of renewable energy installations. Co-design has the potential to provide far greater benefits to the local community by bringing forward ideas for shared land use design strategies and by engaging local creatives in the process.

Community energy projects can also involve stakeholders as a mechanism for micro-investment, providing a means of wealth building for marginalized populations who have been intergenerationally excluded from investment opportunities. Investment in community solar can provide a 7–8% rate of return with little risk. When energy landscapes are shared with other productive uses, that rate of return can be even greater. It is therefore important to think broadly about the distribution of the benefits of every new community energy project and to engage with residents to identify equitable wealth-building opportunities that may otherwise go unnoticed.

As sites and neighborhoods within our cities and countryside transition into more sustainable development patterns, the idea of an EcoDistrict is emerging. An EcoDistrict is a defined area within a city or county that has set a goal of attaining zero environmental impact while also increasing equity and civic engagement through the built environment and the public spaces that connect us. As the EcoDistricts® organization puts it:

Neighborhoods provide a uniquely valuable scale to introduce and accelerate investments that can achieve profound improvements in equity, resilience, and climate protection. Neighborhoods are small enough to innovate and big enough to leverage meaningful investment and public policy.

Such an approach to urban planning is critical to the success of investment in civic infrastructure in support of a Green New Deal or American Climate Contract. Being a cherished contributor to a sustainable and resilient city is part of a good 21st century business model.

Step 1: Building a Community Outreach Team

Every community energy project can benefit from having a community outreach team. Members of the team will benefit from having previous community organizing or public meeting facilitation experience, but such experience is not necessary. The community outreach team will both learn from the community and provide new information to the community in ways that nurture growth and camaraderie. A moderated panel discussion with local leaders and audience questions is a good way to bring forward issues of climate change, environmental justice, energy democracy, and creative placemaking.

Select a Community Outreach Director

The director of the team is in charge of researching the review and approval processes with city or county commissions and permit offices, gaining and using knowledge about best practices in renewable energy design and installation, meeting in person with key project stakeholders, and facilitation public forums during which information can be gathered through storytelling, surveys, and interactive design activities.

With assistance from their team, the outreach director will ensure that the project contributes meaningfully to a regenerative transition that is environmental, social, civil, educational, and cultural.

Identify Local Stakeholders

This list can include:

- community development corporations

- business leaders

- arts organizations

- faith-based organizations

- neighborhood associations

- local nonprofits

- environmental justice groups

- area professionals such as architects, artists, landscape architects, social workers, and community organizers

- individuals who have a record of participation in public meetings

Begin the Community Outreach Process

As soon as a project financing is in place (and sometimes before) it is a good idea to host a well-advertised information session about the project and its goals. Connect with the attendees and follow up with them to build your network.

Make a list of community-based organizations and knock on doors within a 10-minute walking radius (or ¼ mile) of the sites under consideration.

Make a list of engaged residents and business owners and keep them apprised of the planning and design process through periodic newsletters (both email and standard post).

Explain your plan and ask people questions such as the following:

- What do they know about the sites under consideration?

- Do they have any stories to tell about the neighborhood?

- What are their opinions about energy and about their utility?

- Where does their energy come from?

- Would they be interested in being involved in the process and would they like to be provided with updates as the project progresses?

- What ideas do they have for adding value to the project? For example, is there a way to design in a community garden component as a shared site use for some element of the plan?

- Would they be interested in being a part of the project as an investor or advisor?

Involve the Community Throughout

Schedule regular public meetings to talk about the potential impacts of your proposed infrastructures on the surrounding community and to seek fresh ideas on how to make it better.

Make a concerted effort to reach out to the following types of organizations and people and encourage them to provide feedback on the plan at milestone stages in the design process.

- Community development organizations and citizens groups

- Office of Public Art or the local equivalent

- Neighborhood or city historical societies

- Grassroots cultural organizations and church groups

- The local chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA)

- The local chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA)

Consider how the public will use the site during the life cycle of the installation. Consider incorporating civic amenities that can add social value to the project over generations.

Step 2: Identify Viable Sites

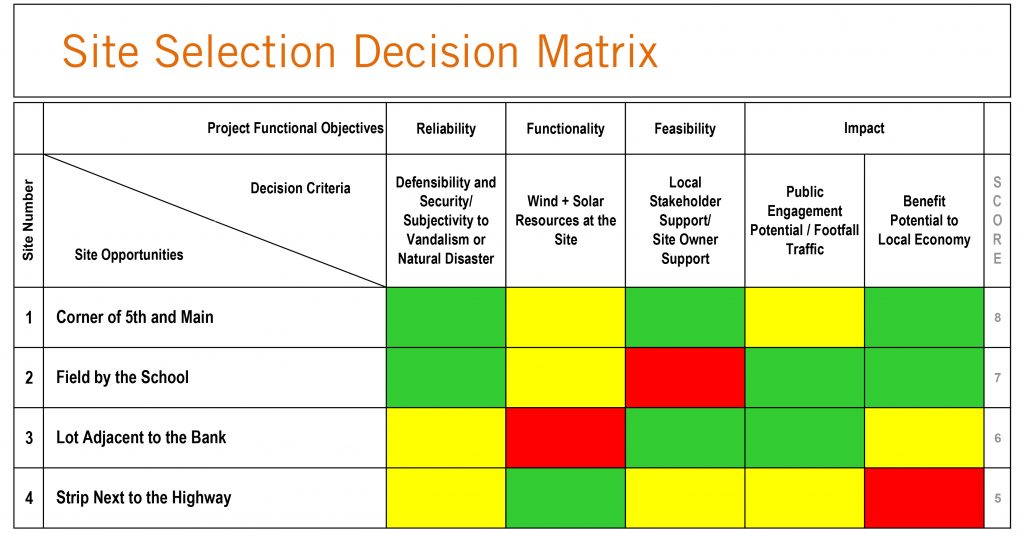

When there are multiple potential sites under consideration, put together a site selection decision matrix using criteria that you develop together with key project stakeholders and community advocates. A simplified example is shown above of what this might look like. One benefit of going through a process such as this is that if there are questions in the future from people who were less engaged early on, this kind of systematic approach can be useful to explain why decisions were made. Your team will arrive at a site selection tool that has its own unique set of decision criteria and project objectives.

Consider aggregating multiple sites to get closer to the economies of scale that are possible in exurban energy installations. By engaging the installer on a larger project, you’ll reduce the cost per installed watt capacity, even if the contract is for multiple locations.

Factors to Consider when Evaluating Merits of Potential Sites

When looking at the merits of sites, think about the suite of available natural energy resources that exist. For example, after reviewing the readings from an anemometer that you installed on the site, a project that you originally assumed would consist of a solar array may also benefit from the installation of a vertical axis wind turbine at the far corner, adding a more consistent output during overcast days. Creative methods of energy harvesting may offer opportunities to engage the public.

In the process of this kind of deep site analysis, you will uncover history, stories, and new opportunities. A project that at first may have consisted of a walled-off nondescript utilitarian energy installation might be transformed into a place of civic pride, a place where new history will be made and new stories will be told, a star in the global constellation of multifaceted solutions that will help us to transition from a culture of exploitation and consumption to a culture of stewardship and conservation. At the end of the day, this approach to smart grid planning will bring social, educational, and cultural benefits in addition to adding resilience and reducing the carbon footprint of our cities.

Step 3: Community Design

Consider two community solar installations on vacant lots near residential neighborhoods at the edge of the city.

After getting all the necessary permissions and permits, one installation places their solar panels on the ground over a gravel lot and protects the project with a chain link fence topped with barbed wire and security cameras.

The other community solar installation begins by presenting the project to neighbors at a public meeting in the nearby school cafeteria, during which ideas are discussed that could improve the design. A local artist agrees to collaborate by collecting stories about the history of the site. Ideas are shared with the project’s community outreach team. Capital investment is diversified with small stakes purchased by area businesses and individuals. A local family foundation comes on board to support the cultural components of the installation. With so much public support of the project, the site becomes the catalyst for the development of a city-council endorsed eco-district.

In the end, the solar panels are installed over a beautiful brise-soleil designed and constructed with help from the community. At ground level is a new public park with a bench surrounded by a garden of shade-tolerant local woodland wildflowers. The names of the stakeholders can be found in a mosaic paving pattern, and the history and future of the site are told through a Solar Mural® installation that marks the entrance to the energy landscape park.

Both community energy projects have done well to increase resilience of our electrical grid and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. One project, however, has also advanced the entire energy transition movement by associating community solar installations with neighborhood beautification. People start visiting the new solar power park from other neighborhoods, which is a boon to local retailers and restaurants.

This highly contrasted example is intended to illustrate that there are many ways to imagine the built manifestations of distributed energy infrastructures. While the primary reason for the existence of a community solar installation will likely be the cost-effective production of renewable energy, whether intended or not these energy installations also exist as cultural and visual signifiers of place and identity. They will alter the experience of those who pass by or linger in their immediate surroundings. They will work their way into the lives and the stories told by the neighborhood and endure in collective memory.

As a consequence of being formally engaged and listened to, the people who were involved in the design process will feel a sense of pride and ownership of the installation and a stake in its long-term success.

The community energy project will benefit by seeing opportunities that would have otherwise been missed. All the best practices of creative placemaking, urban design, and civic art should therefore ideally be brought to bear on renewable energy projects that will have an impact on the long-term value of public space.

Step 4: Expanding the Number of People Invested

Anyone can invest in a renewable energy project and there are many reasons to consider renewable energy as a cornerstone of long-term personal savings. They have rates of return that rival index funds, are extremely low risk, and have low volatility.

Possible investors in your community energy project include:

- Local residents (small investments)

- Business owners (small and medium investments)

- Energy cooperative (governed by a local board)

- Community development corporation (with a strategic plan)

By expanding the investor base in this way, people who may otherwise have objected to the project will instead be vested in its success, and the benefits of the new smart grid infrastructure will accrue to a broader and more diverse stakeholder community. The added complexities of administration will be outweighed by the benefits that will come over the lifetime of the investment as those who live and work in proximity to the project act upon their feelings of pride and ownership in it.

Artist Team: Robert Flottemesch

Energy Technologies: bifacial solar photovoltaic

Annual Capacity: 6,633 MWh

A submission to the 2019 Land Art Generator design competition for Abu Dhabi

Energy Projects as Economic Development Opportunities

On the same area of land, a renewable energy project can give back a pocket park, a picnic shelter, a work of public art, an amphitheater, a river walk, or an educational experience.

By expanding the program of the site, it is also possible to expand the public support and funding mechanisms. While expanding the program and setting a higher aesthetic bar for a community energy project almost certainly means expanding the budget, this method of planning can result in additional revenue models for income beyond the sale of kilowatt-hours or renewable energy credits. It can open access to philanthropic support, grants for public art, and partnerships with institutions and organizations that can lend support to the business model of the new productive landscape. It also means a more seamless permitting and approval process, especially for contested sites in populated areas.

Consider some of the following methods:

- Employ a local artist and other local creatives to drive a central feature of the design

- Use the services of an architect and a landscape architect for every venture

- Sponsor a design competition using a design brief that meets the goals of the project business model and includes the input of local stakeholders. An international design competition brings international attention to a development.

- Give back 1% or more of construction cost to the arts or developing innovative business models around greater productivity from the shared use of landscapes.

By showing a multifaceted benefit to a broad swath of the public, energy developments can become more integrated into the surrounding communities and their legacy can be intertwined with local history and culture.

The intersection of energy and art is certainly not new. At the advent of electrification, most power plants were located by necessity in the heart of our cities because voltage could not yet be raised high enough for efficient long-distance transmission. Consequently, many of the old power plants were designed as beautiful contributions to art and architecture. Many have rightly become heritage buildings and historic monuments, like Battersea Power Station in London, and have been adapted to new uses following their decommissioning. As the new forms of energy generation that do not pollute the air make their way back into our cities, we can design new monuments to this important time in human culture. By thinking creatively, we can bring solar power to sites where it may have otherwise seemed impossible to get approval. By creating beautiful places that also serve our energy needs we can also form a lasting and positive connection between popular culture and clean power.

Step 5: Detailed Design and Tender for Implementation

Once you have financing, site control, and a community vetted design concept in place, it’s time to work with a design professional to put together a set of drawings for tender. Ideally the architect and landscape architect will have been on the team from the start, but if they are coming onto the team later, be sure they also arrange to meet directly with the community before they complete their work.

Once drawings are complete, put out a call to local area solar installers and contractors. Make sure to work collaboratively with key stakeholders on the development of the bid package. Your architect will guide you through the process of contracting and the pros and cons of design-bid-build, design-build, or integrated project delivery models.

At this stage, clearly defining the scope of work and the community-generated plans for shared uses of the site will help to ensure there are no surprises as the project proceeds and that the proposals you receive from contractors can be evaluated fairly.

Community Energy Design Consultant

An emerging field

The Land Art Generator initiative is dedicated to working at this exciting intersection of energy landscapes and social justice. We consult on the planning of urban and rural clean energy infrastructure that seek to provide co-benefits to communities. To learn more about our work go to https://landartgenerator.org or click on the HOME button above.

It’s time to expand public perceptions of what renewable energy power plants look like by taking an approach to the development of new sustainable infrastructure that is informed by the practice of creative placemaking, public art, and participatory design with communities.

Other Resources

There are many resources available to developers who see the benefit of a multifaceted approach to energy projects. These include the Project for Public Places, who provide guidance through their Eleven Principles For Creating Great Community Places, the Trust for Public Land, who published the Field Guide For Creative Placemaking In Parks, the American Planning Association, EcoDistricts®, who provide protocols and certification for city makers, the American Society of Landscape Architects, the Landscape Architecture Foundation, who host the Landscape Performance Series of online resources, the National Endowment for the Arts, and Art Place America, a collaboration of foundations with an excellent set of resources, including the field survey Farther, Faster, Together: How Arts And Culture Can Accelerate Environmental Progress.

A version of this article appears as part of the Clean Growth Template a publication of the Center for Strategic Policy Innovation.