WindNest by Trevor Lee is coming to life on SEE MONSTER! The world’s first fully functioning WindNest will be made manifest in the UK this summer, after it was conceptualised as part of LAGI 2010 Dubai & Abu Dhabi, and prototyped in Pittsburgh. With the help of the engineering team at NEWSUBSTANCE, nuanced but critical structural improvements will ensure the UK’s first WindNest will be a slick and highly successful new example of renewable technology.

In the summer of 2022, SEE MONSTER comes to Weston-super-Mare. SEE MONSTER is a retired platform from the North Sea, reimagined by NEWSUBSTANCE in Weston-super-Mare to celebrate the great British weather from this iconic seaside town. Towering 35 metres in the air, SEE MONSTER will form the highest viewing point along the South West coast of England. It’s a part of UNBOXED: Creativity in the UK, a once-in-a-lifetime celebration of creativity, taking place across England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and online from March to October 2022.

SEE MONSTER will also be home to WindNest by artist and landscape architect, Trevor Lee.

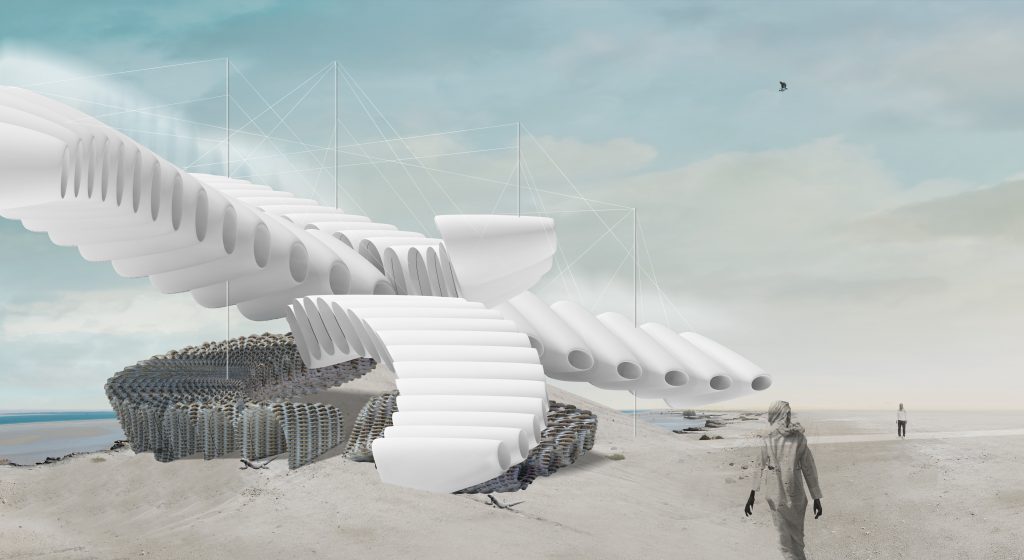

WindNest was originally a submission to the LAGI 2010 design competition for Abu Dhabi. The contemporary sculpture generates electricity using solar and wind power. In so doing, it will eventually offset the embodied energy that it took to design and fabricate it—the qualifying definition of a regenerative artwork. WindNest will be the first full-scale constructed outcome of a Land Art Generator design competition and we could not be more excited!

We took the opportunity of this momentous occasion to speak with Trevor Lee about his approach to design, landscape architecture, and art. You’ll find that conversation below a brief introduction to the history of the project.

WindNest History

The installation of WindNest at SEE MONSTER comes at the end of a decade-long iterative design process that began in 2010 with Trevor Lee’s original design proposal to the first LAGI design competition.

From 2013 to 2016, WindNest was the center of a campaign to construct a regenerative artwork for the City of Pittsburgh with the support of the Heinz Endowments, the Hillman Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Trevor’s concept was identified in partnership with the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy as a work of contemporary public art that would activate the northeast corner of Schenley Plaza, the recently renovated square adjacent to the Carnegie Museum, the Frick Fine Arts Library, and Cathedral of Learning at the University of Pittsburgh. At that prominent location, WindNest would provide 100% of the on-site renewable electricity to power the PNC Carousel in the park, engaging visitors of all ages with the promise of renewable energy to make our lives more beautiful and joyful as well as more sustainable.

Public outreach and educational programming have always been an important part of the project, as it is with every LAGI project. Our educational outreach programs around WindNest have inspired hundreds of young people to think differently about renewable energy and the sustainable design of cities. In parallel with the design development process for WindNest we provided 24 youth workshops along with multiple presentations to community groups.

WindNest at SEE MONSTER provides an opportunity for public engagement at an even grander scale. In May of 2022 we will be opening up a new youth design challenge for a site on the Weston-super-Mare beach and providing in-person and online presentations for teachers.

WindNest is designed to passively rotate to face the wind just like a weather vane. To test the functionality and to experiment with the ball bearing mechanism design, a prototyping team with guidance from Buro Happold and under the direction of GTK Flow Analysis fabricated a 1/4 scale model and subjected it to a series of tests under different wind conditions and speed sequences.

The full-scale installation incorporates a slip ring to allow for continuous rotation while conducting the electricity produced by the turbines and solar fabric. After fluid dynamics testing, the prototype of WindNest was installed on the main stage at the Living Product Expo at the Pittsburgh Convention Center for a global audience, and is now owned by Chatham University.

In the end, despite the letters of support from every local stakeholder, the Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) determined that WindNest was a little too contemporary for Schenley Plaza and so the development of the artwork was placed on hiatus for another five years, until now.

The NEWSUBSTANCE team (the UK-based studio behind SEE MONSTER) is bringing WindNest to life at full scale. Building on the past decade of design development, the NEWSUBSTANCE team has been busy over the past few months developing working drawings and will oversee the installation at SEE MONSTER.

Which brings us back to Trevor Lee, the artist behind WindNest, and our conversation about his work.

Conversation with the Artist

Can you tell us about your early design process? What was your response to the initial LAGI 2010 design brief? And what changed for you when you reimagined your initial concept from 2010 for a site in Pittsburgh (the version of WindNest being installed on SEE MONSTER).

What interested me initially was the idea of a hybrid design approach, the union of technology and ecology. Within the distinct desert climate and landscape of Abu Dhabi, what does it look like to synthesize biodiversity and renewable energy production within a singular but repeatable architectural form? These and other questions of time and resiliency drove the form making and imageability of my design process. The notions of wind and habitat collection, movement and production materialized in the figure of an asymmetrical pod structure, a form able to collect wind energy amidst the changing sand dunes and local habitat. The scale, shape, material and movement of the installation itself would represent a new lens from which to experience renewable energy.

The materiality and function of the pods or nests changed, depending on their relationship to the ground and sky. When in the sky, they performed as WindNests—luminescent white fabric forms, collecting wind and producing energy through their embedded wind turbines. The WindNests were always in movement, constantly self-orienting to the prevailing winds. When the pods were touching the ground, they became habitat nests, providing safe microclimates for a variety of desert creatures. The habitat nests were hand-woven structures, using a known local weaving craft. These structures were made of natural, regionally sourced materials.

This design process and strategy together formed my 2010 WindNest competition proposal.

In 2013, when LAGI reached out to me to consider how to make WindNest a real project in Pittsburgh, I was ecstatic. Transitioning from a future-thinking competition proposal into a real project with site, structural, material, and budgetary constraints was an entirely new proposition. As a practicing landscape architect I was prepared for this iterative design process, but what I was about to undertake was not entirely landscape architecture. The most challenging aspect of making WindNest a reality was selecting the structural approach.

How can the “WindNests” have the appearance of floating above you as they did in Abu Dhabi, but also self-orient to the wind and be structurally sound? Many outdoor installation artists have spent years attempting to make the structure of their artwork disappear from view, to overcome the laws of physics in order to achieve a sublime moment. This was also my initial ambition, however, in the early design studies developed in collaboration with LAGI and the engineering firm Buro-Happold, it was apparent that such a simple and hidden design solution was going to be difficult.

The most significant change in the transition from competition to constructed form was that structure had become integral within the design. The vertical steel poles, horizontal stabilizer, the ribs of the pod, and the overall structure of the WindNest artwork were now as much a part of the experience as the pods themselves. I embraced this as an opportunity to express the structure and its integration with the “WindNests,” with their diaphanous fabric skin structure and wrapped photovoltaic bands.

The structure of WindNest needed to be both robust and delicate, initially reminding me of the early fabric aeroplanes of the Wright brothers. My grandparents who lived in Dayton, Ohio, would often take me on trips to the Wright Patterson Air Force Base Museum in Dayton where there were many examples of wood, steel, and fabric airplanes from the early 20th century.

The expression of structure, color, and materiality became important during the design process and in the final iterations of WindNest for the site in Pittsburgh. The redesign and transformation of WindNest from Abu Dhabi to Pittsburgh resulted in an installation that was more infrastructural in appearance but equally as kinetic, energy-generating, and immersive as an art and renewable energy-generating experience. Ultimately, I would like for people to be able to lie beneath WindNest and to look up and enjoy the movements, changing shadow, and sounds of the turbines rotating above.

How have you been thinking about the site context of SEE MONSTER, where your idea will come to life this summer? It’s very different from both of the original design contexts of Abu Dhabi (a sandy desert beach) and Pittsburgh (an historic urban park).

It is so different and so otherworldly that you would almost assume that SEE MONSTER was the competition site and Abu Dhabi is the location of the built work. It is so fantastically surreal that it is challenging to fully appreciate what it will be like to visit SEE MONSTER for the first time. The winds at this location are very aggressive and WindNest will be operating at high speeds, providing near-capacity electrical output. The context of a beached oil rig on the shore, with verdant plantings and several incredible artworks on the rig, will create a memorable experience for visitors that will not be soon forgotten. You will be able to see WindNest from several vantage points, as it spins and moves in response to the prevailing winds and generates electricity.

You received your first degree from MassArt and then went on to study landscape architecture at RISD. Tell us a bit about your background and how you found your way to landscape architecture through art. How does your art roots inform your design thinking?

My mother was a potter and my father has skilled drawing abilities that he relies on from time to time. With my exposure to artistic parents, I always knew that being a maker was something that I wanted to pursue in some way or another. Oddly enough I ended up in the U.S. Army after high school, and at the end of my service I was able to select my final duty station. I selected Fort Devens, Massachusetts, due to its proximity to Boston, an epicenter of higher education.

In my final year of service I knew that I was going to attend MassArt, and I began to build my portfolio. I started my education there in 1993. It wasn’t until I began to take classes in architecture that I discovered what Landscape Architecture was and how important it was going to be as an emerging field in the coming years. I graduated from MassArt in 1997 with a degree in Illustration. I worked as an illustrator and graphic designer for a few years, but I wasn’t satisfied and I had ambitions of pursuing a career in landscape architecture. I wanted to build landscapes and to work outdoors. While at MassArt I had learned about the Rhode Island School of Design and their landscape program and I knew this is where I belonged, I started there in 1999.

The RISD program in landscape architecture was a transformative experience, a rethinking of what design is. The first course was called design principles, a three day a week all-day, semester long course. Here, in a design boot camp style format and intensity, we worked with varying types of materials to learn and explore their inherent physical constraints and opportunities. We learned to design through iterative processes and not preconceived notions. I became aware of artists like Robert Smithson, James Turrell, and the land artists of the 1970s. These artists and others who worked at large scales fascinated me because they were interested in natural processes and their theoretical underpinnings.

My education at two art schools, at both the undergraduate and graduate levels, has allowed me to consider the importance of art within landscape architecture.

Renewable energy infrastructure is a discipline typically thought to belong to the realm of engineering and technology. Why do you think it is important to include creatives in the design process for our energy landscapes?

The technologies and science devoted to renewable energy production will continue to evolve and advance in ways we cannot predict. As an example of what can be accomplished, communication tech has become so embedded in our lives that it is challenging to find the dividing line between our physical selves and our phones, computers, and digital displays. The reasons for this are of course the advancement of these tech devices but ultimately how designers have invented creative ways to hold, touch, see, and experience tech—to demystify and create immersive connections to what is otherwise a lifeless object. The same, I believe, can be true for our infrastructural renewable technologies. It is just as important that artists and designers find ways to connect with, manipulate, and evolve renewable energy production technologies so that these can become meaningful parts of our lives.

What has been the most challenging design detail of WindNest and how was that challenge overcome?

The pivot point or roller bearing from which the two WindNest pods rotate was the most complex element to design and fabricate. The reason for it being a challenging engineering detail is that it must do three things at once. First, it holds the two large WindNest structures on top of the vertical mast. Second, it allows for the two WindNest pods to spin and rotate freely based on the prevailing winds. Third, it creates a hole for a conduit to run though the bearing, to allow for the energy to pass through from the turbines to the output source, and without becoming twisted with rotation. Buro Happold designed two options initially for the WindNest prototype assembly and we ultimately selected the roller bearing as being the most reliable solution. With the construction of the quarter scaled prototype there were still structural issues that needed to be resolved. With the engineering team at NEWSUBSTANCE, these more nuanced but critical structural improvements are being made to ensure WindNest will be highly successful.

Please share your thoughts on what future cities will look like, especially as it pertains to the cultural experience of energy production and consumption.

We are in a time where we are finally, collectively awakening to realize that sea level rise, climate change, and a mass extinction throughout the world are threatening our way of life and the lives of our children. We are losing our most biodiverse regions at an unprecedented pace. With growing climate migration, there is an immense burden that cities will face today and in the future.

I believe that Edward O. Wilson’s “Half Earth” proposition is an achievable one, where half of the earth is preserved for nature and the other half for humanity. Cities have the potential to help shape our understanding of the natural world, of how we consume energy and live more sustainably. I believe that cities of the future will be generating their own energy and will be self-sustaining in ways perhaps we cannot even yet imagine. I also believe that artists and designers will be vital in foregrounding renewable technologies in urban environments in ways that improve all our lives.

Cover image: Rendering of SEE MONSTER by NEWSUBSTANCE. Image courtesy of NEWSUBSTANCE.

Related Posts

2 Comments

Add comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

[…] clima atlántico, una cascada de 10 metros y varias obras de arte cinético del artista Ivan Black. WindNest, el sistema de riego del Monstruo SEE, fue diseñado por el artista Trevor Lee en una brillante […]

[…] in the Atlantic weather, a 10-meter waterfall, and multiple kinetic artworks by artist Ivan Black. WindNest, the irrigation system for the SEE Monster, was designed by artist Trevor Lee in a brilliant […]