In all of the hot takes and detailed fact-checking in the wake of the Michael Moore-promoted film, Planet of the Humans, not enough attention is being paid to the fundamental lack of understanding on display from Ozzie Zehner regarding the life-cycle environmental footprint of clean energy. The author of Green Illusions is a co-producer of the film and is framed by Jeff Gibbs as the “expert” on renewable energy. According to Zehner:

One of the most dangerous things right now is the illusion that alternative technologies like solar and wind are somehow different from fossil fuels. You use more fossil fuels to do this than you’re getting benefit from it. You would have been better off just burning fossil fuels in the first place, instead of playing pretend. —Ozzie Zehner

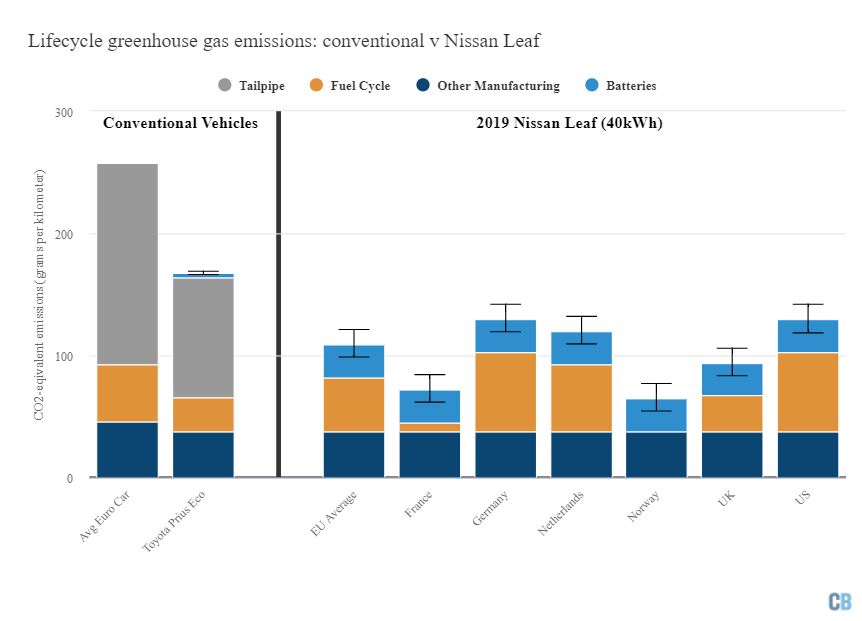

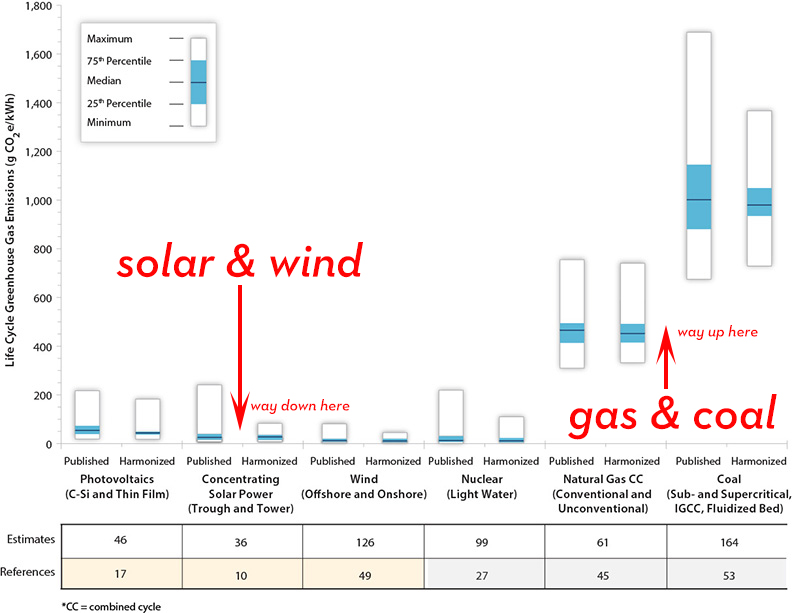

Many fact-checking articles like the excellent piece by Ketan Joshi have focused on putting out the dumpster fire lie about energy return on energy investment (EREI), pointing to the NREL meta-analysis of the life-cycle emissions of various forms of energy infrastructure (image below). It seems that people have been pointing this out to Zehner for nearly a decade, to no avail.

It is simply irresponsible to suggest that renewable energy infrastructures are somehow not an improvement over coal or gas.

But even more fundamentally, what Zehner fails to grasp is the fact that new clean infrastructure replaces the need for new polluting infrastructure. We are going to build new infrastructure either way because old infrastructure gets decommissioned or replaced.

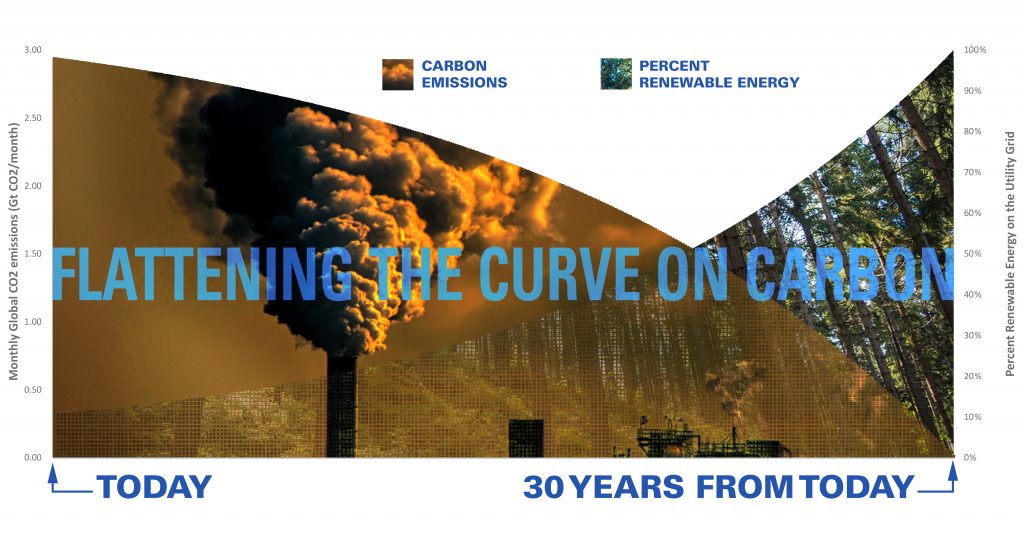

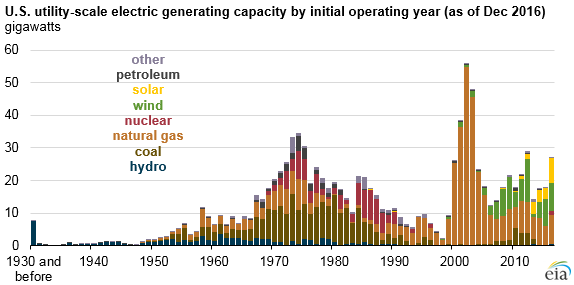

Every year decisions are made about how many new coal plants, how many new gas plants, how many miles of pipeline, and how many new solar and wind farms are going to get built. Each time one of those decisions is made, it commits us to 30 years of using that technology. With only 30 years on the climate clock that means that we should ONLY be commissioning new clean energy sources at this point in time. As you can see in the image below, solar and wind are newcomers and therefore their cumulative capacity is still relatively small. You can see the boom in natural gas in the early 21st century. All of that infrastructure will be aging out in ten years, and if we care at all about the climate we must be replacing it with solar and wind. Fortunately new wind and solar capacity has taken the lead in recent years.

Because we exist today within an extractive petroculture of our own design, it takes mining and fossil fuels to make every piece of every new energy infrastructure, clean or polluting. New gas power plants, pipelines, internal combustion engines, coal trains, oil tankers, LNG storage, exhaust scrubbers, and catalytic converters all have carbon footprints. They all impact the environment. They all take steel, aluminum, copper, silver, and other resources to fabricate and install.

What advocates for a just energy transition are saying is, “Let’s use that same carbon-intense energy (we’re pillaging nature either way right now) to make solar panels and wind turbines and EVs instead of wasting those emissions to make new coal, gas, and combustion infrastructure for which we will need to extract even more coal and gas to operate over the next 30 years.

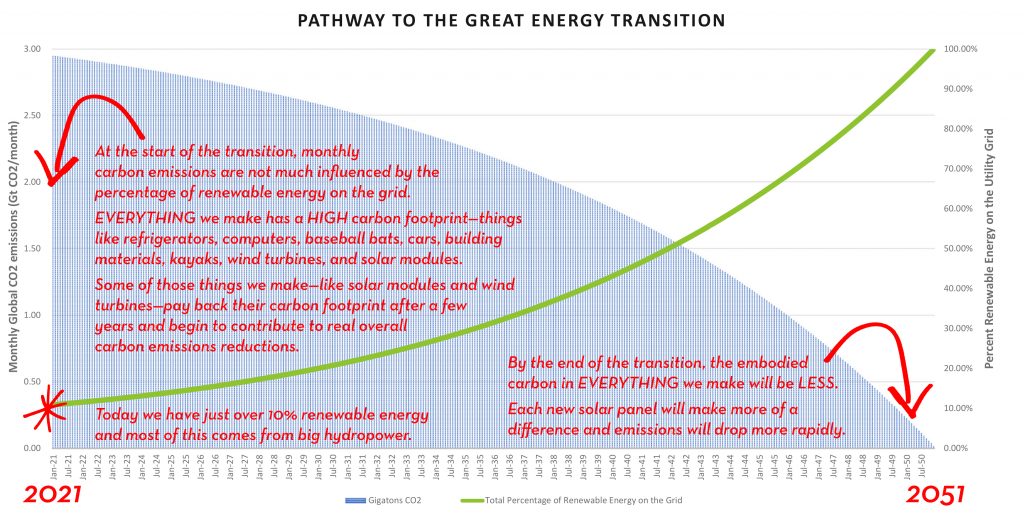

At first, yes, we will use the existing fossil fuel economy to produce the new clean energy economy. But once we’ve crossed over, the return on the investment will accelerate.

Think of the great energy transition like a loan

If we do this right, the great energy transition will look something like paying off a mortgage. In the first couple of years most of what you are paying is interest. Later on you start to pay off more principal with each payment.

In this analogy, “interest” is the embodied carbon contained in new clean energy infrastructure. At first it’s high and it takes 1-2 years of making clean solar and wind electrons to pay it back. But if we make those tough interest payment at the start, eventually the embodied carbon in all things in the economy will tend towards zero as we replace the underlying technology with which we generate all of our energy. To create the graphic for this article, we actually used a mortgage amortization template, set the interest rate to 7% (the rate scientists say we need to reduce emissions by each year), set the principal amount to 500 gigatons of carbon (what estimates say we can still emit and stay under 2 degrees C warming), and set the duration to 30 years (the time we have to transition).

Solar, wind, and water energy infrastructures do not require extractive industries to constantly support their operations. When you build a coal-fired power plant you are locking yourself into yet another generation of mountaintop destruction in order to continuously feed the plant with coal. When you build a solar power plant, the sun shines freely onto the panels for their entire operational life, and it’s the main reason why those EREI chart above from NREL looks so bad for the incumbent systems.

If you’d like to see more direct comparisons in relation to the land use implications of solar vs coal or fossil gas, you can find them in our information graphics section.

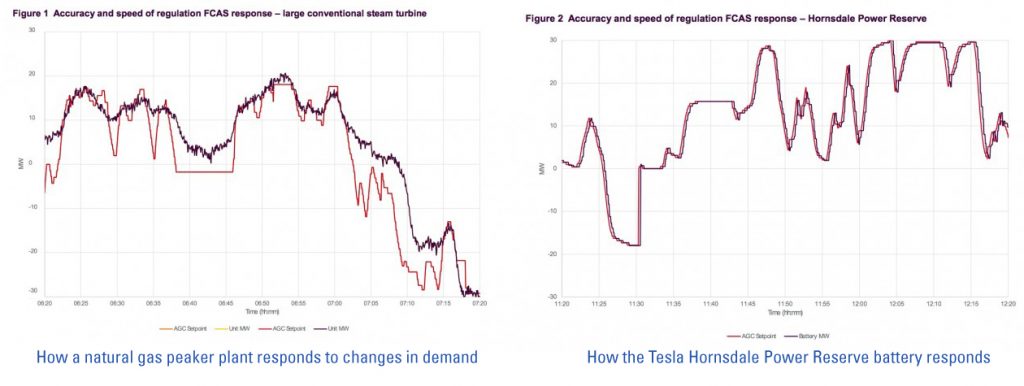

Regarding the issue of intermittency, or the claim that there is some limit of capacity of renewables on the grid. Since the footage in the film was obtained, massive advances have been made in battery technology. Solar + storage is now dispatchable, it helps to balance the grid by responding to rapid fluctuations in demand (and does it far better than gas does), and is now cheaper than new gas peaker plants.

And lastly, even though we make electric vehicles with fossil fuel because we presently live in a petro-economy, EVs—even those driving around in coal heavy power grids—still do have a better environment footprint over their life cycle than internal combustion vehicles. This is partly due to the efficiency of the electric engine, which is about four times that of an internal combustion engine. As the grid gets cleaner, so will electric vehicles.