How to tackle energy poverty, lower greenhouse gas emissions, reduce electricity costs, and increase resilience.

Eighty-four years ago the energy cooperative came into existence as a result of the Rural Electrification Act, which provided a large boon to America’s farmers and ranchers. Today, energy cooperatives could hold the key to the development of dozens of gigawatts of new solar power capacity while simultaneously addressing the issue of energy poverty in America.

Research recently published in the journal Nature paints a grim picture of energy poverty and shows that the United States has made little progress, despite the many well intentioned yet underfunded policy initiatives over the past 50 years.

The financial burdens of energy bills faced by poor families are a serious barrier to their efforts to escape the cycle of poverty. Eight percent of Americans are forgoing food and medicine in order to keep the lights on, and more than 5% of the population are failing in that effort—receiving energy disconnection notices and going without electricity or heat (Bednar & Reames, 2020). Most of the burden of energy poverty falls upon Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, furthering problems of racial injustice in America.

For America’s working poor, nearly 10% of household income consistently goes to paying energy bills on top of other necessary expenses such as housing, food, and medicine, which leaves little for saving or discretionary spending.

At the same time as we are confronted with the intractable problem of energy poverty in America, we are also facing runaway climate change and an aging, non-resilient energy infrastructure.

What if we could formulate a policy proposal that could help to address climate change while also striving to end energy poverty, and making our grid more reliable?

Perhaps the answer lies in energy cooperatives—locally owned by their members, yet federally backed and overseen.

Energy cooperatives are a long established structure for the production and distribution of energy. They are organized around a local region, and they tend to have a community-minded approach to business models and planning processes. They have been instrumental to the success of the energy transition in Germany, and examples can be found around the world.

Energy cooperatives got their start from the Rural Electrification Act (REA) of 1936, which channeled funding through cooperatives.

Each post-war tax-payer subsidized REA energy installation provided “a 60 amp, 230 volt fuse panel, a 60 amp range circuit, a 20 amp kitchen circuit, and two or three 15 amp lighting circuits. A ceiling-mounted light fixture was installed in each room, usually controlled by a single switch mounted near a door. At most, one outlet was installed per room.”

Many of the energy cooperatives established during that time still exist today. The National Rural Electrification Cooperative Association lobbies on behalf of America’s rural electric co-ops and loan guarantee programs continue to support the expansion of rural electricity and more recently, broadband.

Since its early days in 1936, public investment in electrification infrastructure has not been particularly concerned with alleviating the kind of energy poverty that we see persisting today. The original Rural Electrification Act predominantly helped white farmers and homesteaders and did nothing to address the electrification needs of the urban poor or Indigenous people, who—at the very same time as rural whites were getting such wonderful support—were struggling against racially discriminatory finance systems and being left behind by many other New Deal government programs that disproportionately benefited white America.

Today, energy cooperatives provide a means of diversified investment in the construction of new energy infrastructure. An example is the Vineyard Power, which raises money from private investors in order to plan and build solar arrays and offshore wind farms on and around Martha’s Vineyard. The people and companies who invest in the capital cost of energy installations benefit from the sale of electricity from them. It is a model that is typically open to the investor class and not to the people who are struggling to pay their utility bills.

How could the energy cooperative model be applied to help alleviate energy poverty? Cooperative Energy Futures in Minneapolis provides a model that could be greatly expanded if enacted with a federal mandate and additional investment. Their model shows that distributed solar energy is less expensive than centralized grid power, with its large overhead and costly distribution infrastructures. They pass the savings along to their members who do not need to pass a credit score to sign up.

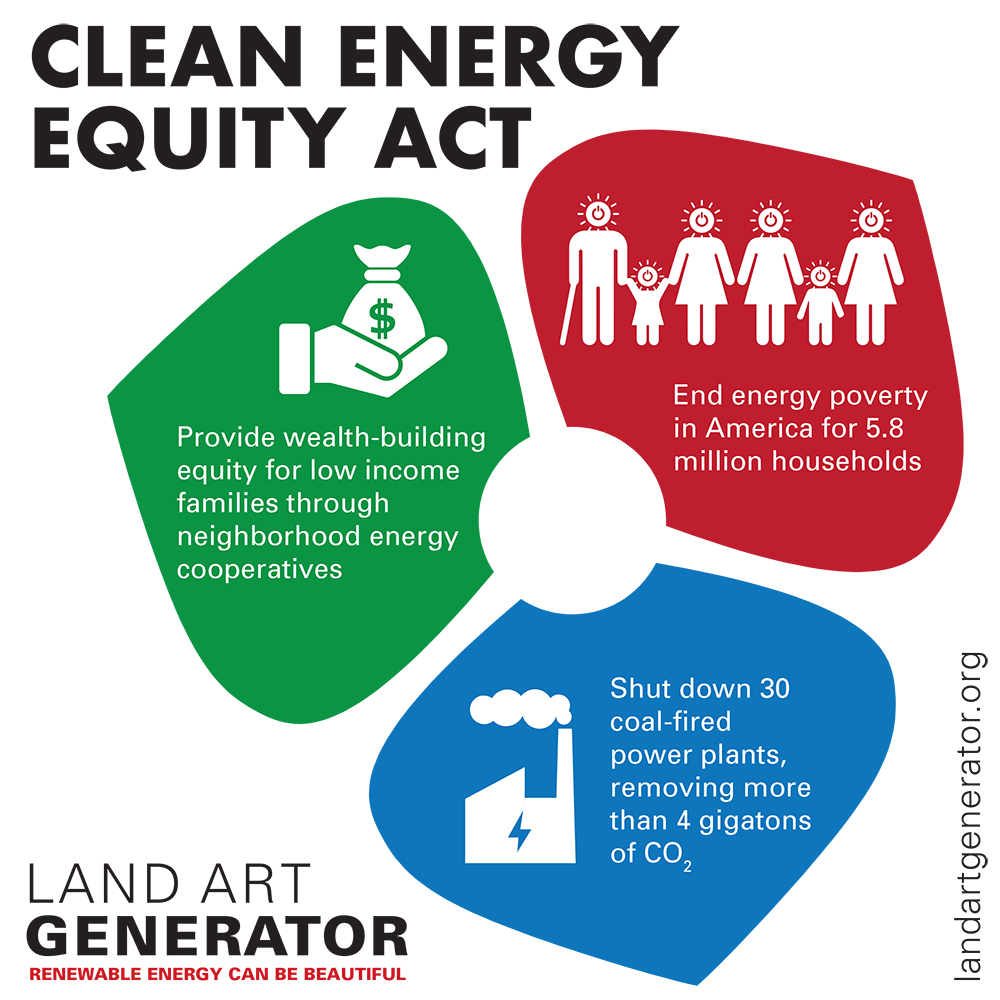

By supporting a new kind of urban and Indigenous energy cooperative through something we are calling the Clean Energy Equity Act (CEEA), we could bring the benefits of our new green energy infrastructure to the families who were left behind as generations benefited from programs like the Rural Electrification Act.

These new energy co-ops will be locally established and governed by neighborhood members. The federal government would provide loan guarantees that would allow for the installation of millions of solar photovoltaic and solar thermal panels on rooftops of affordable housing, on homes and businesses within historically redlined neighborhoods, and establish co-designed microgrid infrastructure on infill lots in areas that are identified as economic improvement zones. Membership would be free and prioritized based on geographic proximity to the energy installations—even targeted at the very households that have received stop service orders in the past five years (those records can be easily accessed).

The cost of energy would be greatly reduced since the program’s bulk-purchase arrangements would result in extremely low capital cost of solar installations on top of low-interest credit, resulting in a price per kilowatt-hour as low as $0.08 for co-op members. The Clean Energy Equity Act would turn energy consumers into energy investors and producers, allowing families to build wealth through the exchange of electricity that is generated within their own community. It gives families who could never otherwise engage in such a capital-intense enterprise the same access to the wealth-building instrument of energy infrastructure that investors like Warren Buffett have today.

The energy cooperatives could also install and maintain behind-the-meter energy storage systems along with smart meters and thermostats to assist with demand management, frequency regulation, and resilience. These added systems would allow for more efficient operation, provide greater reliability with increased renewables on the grid, alleviate the need to build new power plants, and even allow for accelerated decommissioning of old and polluting coal and gas power plants. Those demand management and reliability services have real value. Energy and services sold by the co-op to the grid would accrue to cooperative members through dividends.

The constellation of energy cooperatives could be overseen and assisted with operational maintenance by a new federal agency under the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Close coordination with independent system operators would provide more granular detail as to how and where energy is being generated, stored, and consumed. This model is already underway in California using what’s known as a virtual power plant.

5.8 million households receive service cancellation notices due to inability to pay their utility bills. Installing community solar to power those 5.8 million homes would take an investment of $50 billion—half the amount of the Department of Energy’s Loan Guarantee Program that has greatly benefited private energy investors and companies like Tesla. Additional CEEA loans can be made available for the larger scale community energy installations on commercial rooftops and open spaces, increasing the benefits to co-op members.

The CEEA loans would be paid off through the sale of energy and services. Under no circumstances would an energy cooperative member have their power turned off.

The 25+ gigawatts of new solar capacity that the CEEA would fund would draw down more than 4 gigatons of CO2 each year from the atmosphere—the equivalent of the greenhouse gas emissions of 6.7 billion conventional passenger vehicles. At the same time it will provide the opportunity for millions of low-income Americans to share in the new wealth creation that the great energy transition will bring over the coming generations.

Benefits of the Clean Energy Equity Act include:

- Alleviation of energy poverty

- Elimination of the need to build new centralized energy infrastructures

- Allow rapid decommissioning of coal-fired and gas-fired power plants

- Increasing efficiency of energy consumption through demand management (weatherization assistance programs remain in effect as well)

- A more resilient electricity grid

- Reduce the expense of maintaining grid transmission infrastructures, which is passed down to cooperative members

- Direct climate action that benefits lower income communities

Related Posts

2 Comments

Add comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Great idea! Do you have draft legislation yet? Any interest yet on Capitol Hill? This seems an important component of beginning to help BIPOC communities address ( and redress) institutional racial disparities, and particularly if the fallout from the corona virus epidemic requires greater reliance on home access to the internet for schooling, working, and other needs.

Hi Dave! We don’t yet have draft legislation or interest in government. For now it is a spark of an idea. We’d love to take it forward if you have any recommendations on who to speak with about it.