There have been some detractors to the idea that we can fuel the world entirely with solar energy by 2030. It seems to me from the numbers that this is possible and it’s important that we all recognize that it is possible because we don’t have the luxury of time. There has been some confusion with regard to the 1000 watts per square meter value. Some question this, using figures that they find of 250 watts per square meter. But this lower figure is the average for an entire day. 1000 watts is the measurable value at any one time in direct sunlight which has fallen from 1,366 watts at the outer atmosphere. This entry clears this confusion up if you read it carefully. By using 1000 watts and multiplying this times the hours per year of direct light, we don’t rely on daily averages and arrive at a more reliable figure.

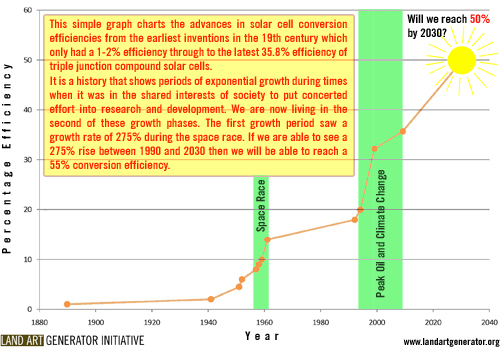

In the map showing the surface area required to do this, I used conservative figures (20% conversion efficiency and 70% cloudless sky). Recent advances by companies like Sharp have achieved 35.8% efficiency in a photovoltaic cell. CPV technology like that from Sunrgi achieves 37.5% by concentrating light and these are not just laboratory numbers; Sunrgi is in production. And remember that it is still 2009. By the year 2030, if we are as focused on solar energy as we have been on computer transistors in the recent past, then some modified version of Moore’s Law will undoubtedly be applicable to the efficiencies of solar energy conversion.

Since 1970 that law has held true in computing that the number of transistors that can be placed inexpensively on an integrated circuit has risen by 200% approximately every two years. If we look back at the history of PV technology, we see that the efficiencies were raised 200% between 1957 and 1960 as a result of the investment in space exploration which requires solar power as the only possible source of long-term energy for satellites and exploration devices. And again we see a 200% increase from that time to the present. If we are able to achieve one more 200% increase between now and 2030, then that means efficiencies of between 50% and 60%. Unless we completely give up (and all evidence points to the fact that more research than ever is going into PV technology), then this is almost an inevitability.

So going back to the numbers on the surface area required, it would be safe to say that a more realistic assessment of the state of technology by the year 2030 would see the square meter number reduced by half. Of course we need to start constructing solar power plants today at the 20%-30% technology and phase in new technologies as they come to the market. But the 2030 number was based on a projection of how much energy will be used in 2030, so the growth both of technology and of BTU consumption worldwide can be seen as happening together.