Renewable energy can be ugly. But it doesn’t have to be.

There has been a resurgence of support in the press for nimbyism lately, especially in the UK. There and elsewhere, the idea of the landscape—both ruggedly natural and idyllically agricultural—holds great significance to the culture and to the history and identity of place. Even when relegated to the urban core for any length of time, one can always reflect on the splendor of nature, and take some solace in knowing that those places are out there at that moment, unspoiled.

A recent op-ed article in the New York Times by Roger Cohen, Britain Goes Nimby, is a nice summary of the state of affairs for renewable energy projects in the UK.

With renewable sources like wind and solar accounting for just 3.3 percent of energy consumption in 2010, Britain is a long way from its target — mandated by the European Union — of 15 percent by 2020.

In theory, green-organic Brits get all this. The Cardiff survey found that 81 percent of people are concerned that Britain will become too dependent on imported energy. Even if fewer people now say there are risks to Britain from climate change — 66 percent today against 77 percent in 2005 (an economic crisis does focus the mind on the present) — they support using a mix of energy sources (74 percent), and 82 percent claim they would “probably or definitely vote in favor of building new wind farms in Britain,” against 41 percent for nuclear power stations.

But that’s before nimbyism kicks in. We live in a nimbyfying world: idealism abounds, propelled by planet shrinkage, but so does ego, inflated by solipsistic online universes. Where they converge is in hypocrisy and humbug.

The thing that is hinted at but never directly addressed in the article (and in those that it quotes) is that the proposed wind power installations which are objected to are never considered aesthetically, nor are they designed to be site-specific. Instead, they are externally designed utilitarian mechanisms—garish objects distracting from the beauty of the places in which they are proposed. But this need not be the case.

Angel of the North, by Antony Gormley | Photo- All rights reserved by Sea Pigeon on Flickr: click image for link.

In fact, one of the articles that the Times piece cites—an article by Alexander Chancellor (When it comes to windfarms, I don’t feel bad about nimbyism) in the Guardian, actually makes reference to Antony Gormley’s Angel of the North, a large £1 million sculpture completed in 1998 that initially drew criticism, but is now seen as an iconic landmark for the Northeast of England in which people take great pride. Its extensive 600 tonne foundation was required to resist the force of the wind on the wide wings of the artwork (it makes one wonder tangentially in the context of energy art whether the wings could have instead harnessed that wind power and lessened the moment forces that resolve into the foundation).

The beauty that is enshrined in museums and galleries, architecture, art and design is widely acknowledged and considered a fit charge on the state. The beauty that is enshrined in nature is not, other than in some farm subsidies, and is perpetually under threat. The Welsh turbines are a reckless tearing up of a carbon reservoir at public expense, pending the development of other forms of power generation. The least those hoping to profit from this vandalism can do is put the related power lines underground.

The power lines should certainly go underground where this is feasible. Buried conduit is much more protected from weather and from acts of sabotage, and it is arguably the most aesthetically appealing alternative. And the wind generators themselves could be designed for their specific site, thinking outside the box, and providing new tools for sustainable development.

Another article in the Guardian, by Simon Jenkins, Bravo for nimbyism. What else will keep us from turbines and pylons?, shows how nimbyist arguments, when juxtaposed with talk of subsidies, can very easily segue their way into reasons why we should devote more investment into natural gas projects.

Another article in the Guardian, by Simon Jenkins, Bravo for nimbyism. What else will keep us from turbines and pylons?, shows how nimbyist arguments, when juxtaposed with talk of subsidies, can very easily segue their way into reasons why we should devote more investment into natural gas projects.

To wreck the fragile landscape – and seascape – of Britain when the future more probably lies in gas, sun and waves seems idiotic.

Which leads also to the shift to offshore wind. It is generally acknowledged that utilitarian turbines are less offensive when set against the distant skyline of the sea than when seen marching along mountain ridges. But offshore wind farms are vastly more expensive.

From Roger Cohen’s piece in the New York Times:

So, at about twice the price, Britain is now being forced to build most new wind farms offshore. In 2010, onshore installations dropped 38 percent compared with 2009, while offshore ones tripled. All the added cost of that undersea cabling will one day be billed to someone.

For less than twice the price I’m sure that we can come up with other land-based solutions to harness the power of the wind that can appeal to the aesthetics of the communities near which they are constructed. Perhaps they can even come serve as proud landmarks of each place (much like Gormley’s Angel), specifically designed to merge with and compliment the landscapes into which they are sensitively placed.

Below are just a few examples of site-specific, wind energy generating public artworks from the 2010 Land Art Generator Initiative design competition. Maybe one of these designs is adaptable to northern Britain or anywhere else that finds objection in massive horizontal axis wind turbines. The 2012 design competition for New York City will bring with it many more wind energy designs.

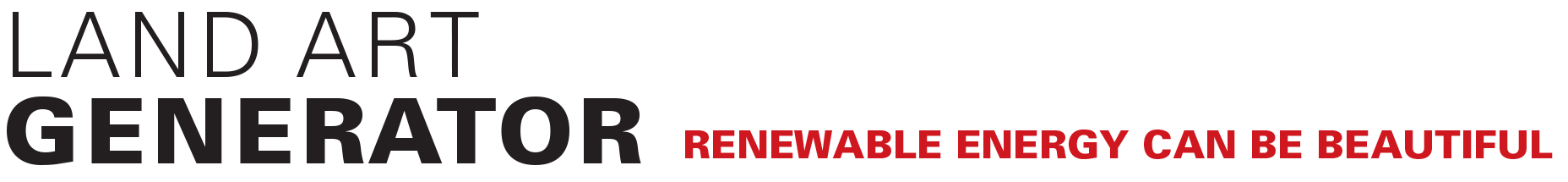

Windstalk by Atelier dna – click on the image for more information.

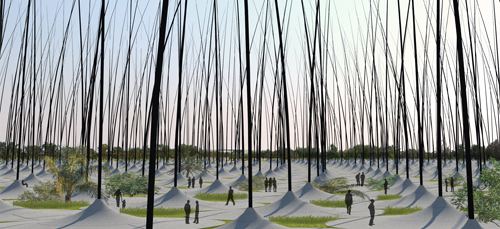

WindNest by Trevor Lee and Clare Olsen – click on the image for more information.

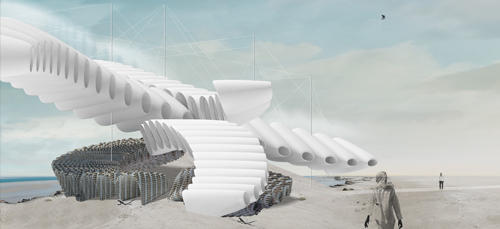

i Leaf Green by Maria José Zapiain Gonzalez and Rodrigo Segura – click on the image for more information.

Weather Field by Lateral Office (Toronto) + Paisajes Emergentes (Medellín) – click on the image for more information.