Below is a news article that someone mailed to us from the year 2040. We’re not sure how. But we are very heartened to see that—two decades hence—such rapid progress is possible towards energy and environmental justice.

Los Fotónes, 2040

January 21, 2040

CommonNews San Juan

In a small informal settlement called Los Fotónes, the future is already here. Guided by Dr. Vera Clemente, a researcher at Escuela de Artes Plásticas y Diseño de Puerto Rico, the CommonNews team took a behind the scenes look at the promise of a new solar technology that has the potential to bring a long era of peace and prosperity to the world.

As we make our way from the road, the wind rustles the leaves of the Jackfruit trees. After a few minutes we begin to see the experimental canvases of solar paint lifting and falling gently in the clearings. When we reach the entrance Dr. Clemente introduces us to Victory Alcado, one of the founding residents of Los Fotónes, and Clemente’s most important local partner. Before getting a lesson in how the new technology works, we sit down for a cup of locally grown coffee and reflect on the recent rapid progress that has made the energy transition possible.

There was a time earlier this century when things changed more slowly and when the promises of technology to do social good were frustrated by massive inequality and an austerity-minded public sector. We are fortunate—following the tumultuous decades behind us—that the balance of power has now shifted from corporations to the people and structural incentives now favor degrowth. With the nation’s economy shifted from capitalism to terrametrism, we finally have a standard of value underpinning wealth that is based on measures of ecoregional health and civic engagement.

Wealth is now created when ecoregions, habitats, and the atmosphere are restored, and it is lost when they are damaged. Wealth is created as social cohesion is enriched. This is the reverse of our previous system that rewarded only profit, where wealth could only be created through wage labor, and where businesses were structurally disinterested in the stewardship of the earth’s ecoregions.

After ten years of terrametrism, we have finally turned the page on wage-based capitalism. The time-saving benefits of quantum technology and a rapidly renewable circular economy without scarcity are being shared by everyone through disbursements to our terrametric wealth accounts.

The progressive structural changes to our sociopolitical systems are in large part due to the potency of one technology: solar power. Access to affordable distributed energy was one of the important catalysts of the Great Capital Inversion that ended the struggle of wage labor and allowed a steady state global system to evolve within the safe carrying capacity of the Earth’s natural resources.

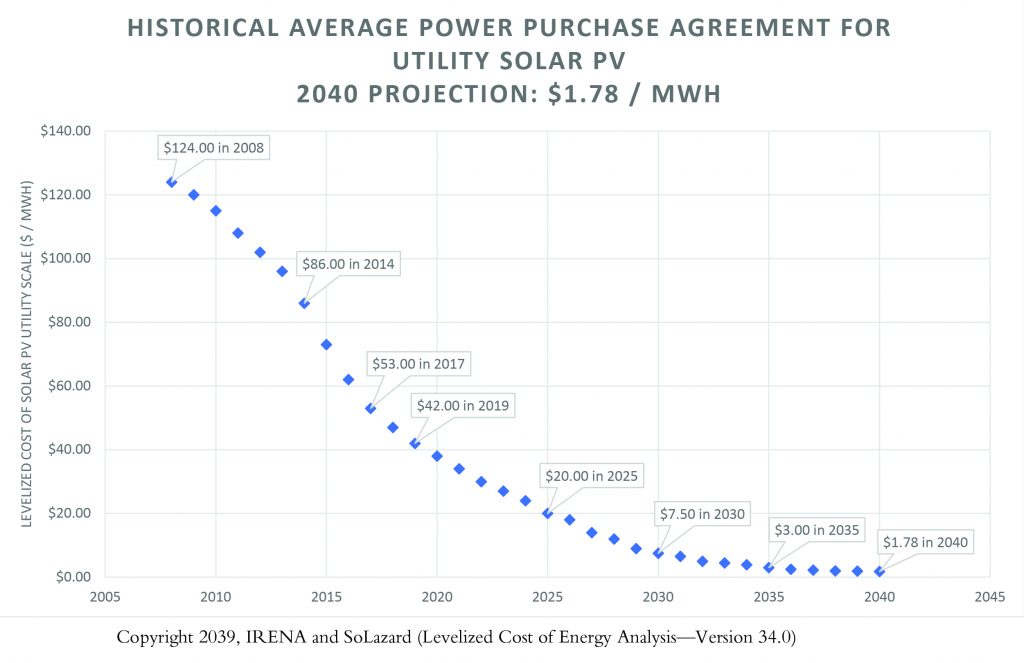

According to a report published yesterday jointly by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) and Solazard, solar power passed yet another milestone in 2039 as the cost of installed residential solar broke the $0.70 per watt barrier and the cost of utility-scale solar approached $0.25 per watt. The power purchase agreement (PPA) cost of solar power on the grid has reached a ridiculously low rate of $1.80 per MWh ($2.60 per MWh with storage) in a major deal inked by the City of Dhaka just before the big quantum dot dropped, ringing in the new decade.

Ten years ago, solar power was a major factor in bringing about, but also easing the economic burden of the 2028 collapse of the carbon bubble. As the last of the dinosaur investors took massive hits from stranded asset write-offs, the low cost of solar energy resulted in massive gains in productivity and innovation within an emerging circular economy driven by the 100% employment program, safe welcome borders, and the Civilian Solar Corps. The past decade’s expansion in solar deployment and the economies of scale and innovation have brought solar power to roughly 1/10th the cost of old petro-energy and fossil gas.

While we might be tempted to rest on the laurels of the past decade, there is still much work to do, especially in shipping, industry, and construction (the SIC sectors) before our global carbon emissions are down to zero. Nine gigatons per year may be less than a quarter of what we emitted in 2019, but we are still getting dangerously close to passing 500 parts per million of CO2 in the atmosphere. With technology lagging on meeting the replacement for SIC sectors, it is more important than ever that we keep driving down the cost of solar for all uses.

In what looks to be very good news on that front, interdisciplinary research out of Escuela de Artes Plásticas y Diseño (EAPD) de Puerto Rico and the University of Buffalo has demonstrated the long-term reliability of 100% non-toxic, organic, perovskite solar paints (PSP). According to Dr. Clemente, “PSP can be installed (painted) on any surface using the same technique as house paint. It can be made clear or in a variety of colors. It can be color matched and can be blended together in-situ as an art composition, much like traditional paints.”

We were fortunate to witness this new technology being tested at Los Fotónes by the founders of the informal settlement, led by Alcado, the charismatic 20-year old who is now taking courses at EAPD. Los Fotónes is what’s coming to be known as a communovoltaic landscape because it houses people who can make a living harvesting solar energy—or as Alcado likes to call it, “photon farming.” During the research stage, the new technology has allowed Los Fotónes residents to experiment with a new business model leasing fully charged portable jackfruit batteries to locals. A second demonstration site is the nearby Aerostatic Balloon (Globo Aerostático), where solar paint has replaced the balloon’s previous exterior coating and has given a second life to the tourist attraction as a power plant that feeds 300 MWh per year into the local microgrid. A third demonstration is just getting started closer to San Juan at an encampment by the name of La Granja.

So how does it really work?

According to Alcado, “After the designated setting time of the solar ink, the painted area begins to generate a charge in sunlight that is collected using leads attached to the two furthest points on the surface. The conversion efficiency declines slightly after the first few years, but at any point a new layer of solar paint can be applied to revive the efficiency.”

Over time, solar paint is encapsulated beneath new layers, just as paint is covered over on a house. At the end of its life cycle, when removed from the substrate, the dry solar paint is heated with a solar oven, which separates the component parts for use in new batches of solar paint. If discarded without recycling, it bio-degrades into natural materials that make excellent fertilizer. It’s the perfect terrametric product.

Alcado demonstrates the function of SolarPaint by clipping a GaN contact onto the side of the wall of their house near the entry door, and another GaN contact onto the far corner of the same wall. Between the leads is an electron gathering area of about 10 square meters. After about an hour of us talking, a nearly empty 3 kWh jackbok (a jackfruit aerogel battery)—enough to keep your fridge and thing-printer running for the day—now shows a full charge. Alcado says she stewards the solar paint and energy harvesting of just over 2,000 square meters (½ acre) of solpainted elevated canvas, which keeps 305 of those lightweight portable batteries charged every day. Her family uses no more than five jackboks for their own household and can lease out the other 300 jackboks on a rotating schedule.

The residents of Los Fotónes make the batteries themselves using the wood and the fruit from the onsite jackfruit orchard. After a jackfruit is eaten, the inner pulp is heated with a concentrated solar thermal furnace to create an aerogel with incredible supercapacitor qualities. It takes a few minutes to wire each aerogel and affix it into the wooden case. Los Fotónes residents have found the aerogels last longer than was originally suspected. They tend to have more aerogels on hand than they need to replace the depleted ones.

Los Fotónes jackbok batteries fit any size E-Rover and can be plugged into any residential microgrid. You can lease one 3 kWh jackbok for fifty cents plus a refundable deposit for the beautifully carved jackwood case. The 15 kWh module ($2.00) is more than enough to run a high-energy household or business and get you most everywhere you need to go on the island (even one 15 kWh will get you about 50 miles of range). You can hang out at Los Fotónes Hash and Coffee Bar if you’d like to wait for a half-price top up. Hot tip: the misolein soup is exceptionally good!

One Indigenous cooperative that is marketing a version of solar paint under the Public Licensing Act (PLA) estimates a starting price point of $0.15 per watt later this year and they expect to be below $0.10 by 2045. Per the PLA, a percentage will be given back to the universities and researchers who worked on it, and to the public sector funds that led to the discovery. Due to the abundant and recyclable natural materials in the product, PSP will soon be less expensive per volume than commercial paint, the cost of which has been rising slightly due to the more stringent circular economy and red-list product standards that the administration put in place to increase terrametric wealth. Our contact at the cooperative, who asked to remain anonymous, says they are already in partnership with one of the cities bidding on the 2043 world EXPO although they wouldn’t say which city.

Another interesting feature of the jackbok battery is the information that it gathers from the microgrids to which it is connected. When batteries are returned, the residents of Los Fotónes first scan the data for any potential electrical irregularities that were encountered, which could mean they were connected to an unbalanced or inefficient system. They then send those flagged reports to jackbok users whose microgrid they pertain to, after which the data is anonymized per the strict standards of the Cyber Privacy Act, which was enacted following the 2020 pandemic. The data is fed into the Puerto Rico Commons quantum computer energy model which can flag potential efficiency issues by looking for non-conforming bits. These information services (and the coffee shop) augment Los Fotónes’ income from battery leases.

Residents of Los Fotónes expect to have an expanding market for some time—at least while solar paint gets rolled out around the world. Even then, there will remain denser urban environments like San Juan where there just won’t be enough painted surface area, and where folks will take a drive or catch the OWCAT (oscillating water column area transit) and the electric sky car out to the communivoltaic farms of the interior to swap out their jackboks for the month and to take in some rewilded nature.

The best part about Los Fotónes are the vivid colors. They are everywhere around you! As each area of this energy landscape accrues solar painted layers, amazing textures and patterns emerge through compositions that tell stories of Puerto Rico’s past and future. It seems our world will soon be visually enriched by a powerful tapestry of cultural expression—a painted world of wonder where the street art and the graffiti art are the power plants of our cities.

Soon anyone will be able to paint the roof or walls of their house for a few hundred bucks and have free power. Every single surface that used to be painted with commercial paint will soon be painted with solar paint, charging non-toxic portable batteries that circulate in a new economy where energy is currency.

Over the past decade, places like Puerto Rico on the front lines of climate change have demonstrated how access and agency around affordable energy and its means of production can liberate people and restore a balance of power in society. As we embark upon an era in which anyone, anywhere can convert almost free energy into circular goods and services, we should expect to see new sources of social wealth emerge alongside a recovering natural ecosystem within a rightair atmosphere that we will have more free time to savor!

—Robert Ferry

References

- The concept of solar paint is written about here with some ideas of how it could become reality.

For the estimates of what solar electricity will cost in 2043, see the following links:

– https://grist.files.wordpress.com/2011/04/grid_parity.jpg

– https://www.pv-magazine.com/2016/06/15/irena-forecasts-59-solar-pv-price-reduction-by-2025_100024986/

– https://grist.org/solar-power/2011-04-05-solar-is-contagious/

– https://www.solar-united.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/RE_Technologies_Cost_Analysis-SOLAR_PV.pdf

– https://www.irena.org/costs/Charts/Solar-photovoltaic

– https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/solar-pv-prices-to-fall-below-1-00-per-watt-by-2020

During the writing of this piece, which in reality (to be honest) took place in the spring of 2020, news broke about a power purchase agreement (PPA) in Abu Dhabi of 1.35 U.S. cents per kilowatt hour (kWh) or $13.50 per MWh, which is already aligned with my projected year 2027 average: https://www.forbes.com/sites/dominicdudley/2020/04/28/abu-dhabi-cheapest-solar-power/ - How perovskite will steer the next major cost per watt drop: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/11/everything-you-ever-wanted-know-about-perovskite-earth-s-most-abundant-type-mineral-we

- The use of gallium nitride (GaN) as conductor: https://phys.org/news/2016-07-highly-materials-efficient-electronics.html

- For an example of carved jackwood see: https://travellingartist.wordpress.com/2011/11/07/jackwood-art/

This piece appears in the collection of short stories and essays, Cities of Light: A Collection of Solar Futures, Edited By Joey Eschrich and Clark A. Miller and recently released by Arizona State University. The project is the outcome of a multi-day workshop held at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado at the end of February, 2020 just before the start of the coronavirus pandemic lockdown.

Visit the Cities of Light website to download your copy of the complete book! It’s available as PDF, e-book (all kinds), and print-on-demand.

Header image: Jackfruit fabric, in colour Botanical Green, from Sanderson’s Glasshouse collection.